This is a review I wrote on Amazon.com of

Permanent Parisians: an Illustrated Guide to the Cemeteries of Paris, by Judi Culbertson and Tom Randall (Robson Books, 1986).

I can’t help but agree with the other reviewers on Amazon.com: this book is entertaining and certainly the only serious guide in English to the cemeteries of Paris.

The fact that I was disappointed in their failure to include either of the two major cemeteries in Florence in their Italian book, in particular delle Porte Sante, the resting place of Collodi as well as stunning funerary sculpture, did not preclude me from using their volume

Permanent Italians while living in Italy this past year. And after moving to Paris in August of 2006 I was lucky enough to find a used copy of their

Permanent Parisians (1986 edition); I then set about documenting the statuary in the cemeteries of Paris.

At first I started out my research in Parisian cemeteries using only the “tours” outlined in the Culbertson/Randall book, and with one exception found their maps are right on the money. (The one exception is a small but important point: on the map of tour no. 4 of Pere Lachaise in division 89, the Delage family, listed as “J”, should actually be located in the center of the division not at the corner).

Some weeks later, while poking around a local bookstore I came across Bertrand Beyern’s

Guide des tombes des homes celebres (2005, in French only). Beyern, a local tour guide of Parisian cemeteries, has documented many of the major personalities in cemeteries throughout France, not just in Paris, and is one of the leading authorities on Pere Lachaise, the primary focus of my work. I also discovered the excellent map of Pere Lachaise produced by “Editions Metropolitain”, and available for purchase just outside the entrance to the cemetery. Those resources along with the half-dozen or so superb French websites covering Parisian cemeteries proved very helpful in locating specific individuals. It was after the first several weeks of my work in Pere Lachaise, as well as a number of other cemeteries in the city that I realized there were a number of problems with the Culbertson/Randall book.

(Unfortunately, their publisher, Robson Books, an imprint of Anova Books, never responded to my request to contact the authors. I suspected that some of the problems I discovered might have arisen since their book was written some 20 years and thought a correspondence might have been of some help here.)

Naturally time changes things: earth shifts, things move, and sometimes graves disappear in cemeteries. For example, one of the most striking monuments in Passy cemetery as described in both Culbertson/Randall and Beyern is that of Antoine Cierplikowski. Unfortunately the stone is, well, gone. Not just the statue but also the entire grave.

And even the headstones themselves occasionally change over time. In division 22 of Montmartre cemetery Culbertson/Randall describe the dancer Nijinksy’s grave as under a “plain arched stone”, when in fact today there is a fantastic life-size sculpture of the deceased in what appears to be a harlequin outfit.

There were a few typos.

Douvin in div. 32 of Montmartre should in fact be

Dauvin; and the correct spelling of the name is in even in their photo on p. 129. In St. Vincent’s cemetery they list the statue over the tomb of Rene and

Jean Dumesnil, when in fact it should read Rene and

Jeanne. (Jean is a man’s name, Jeanne is a woman; a rather important distinction here). This is the same statue found on the cover of their 1986 edition. I also found it curious that the photo of Theodore Gericault in division 12 of Pere Lachaise was reversed.

I also thought it odd they didn’t mention the famous American silent film star Pearl White (as in the

Perils of Pauline) who is buried in Passy.

On a more serious level I found the tendency of Culbertson/Randall to mention individuals in the text and then not place them on their maps quite frustrating. Frankly I thought that was sloppy and made me wonder if was less a guidebook than a series of amusing anecdotes about famous and the near famous buried in Paris.

Passy is also my favorite cemetery in Paris: the unique statuary and fantastic stories, all packaged together into such a small place that is hardly ever visited by the tourists, is a real treat. But Passy symbolizes one of the oddest problems with the Culbertson/Randall book: their map of the cemetery is wrong. Or rather it is their divisional layout that bears little resemblance to the actual official cemetery layout today. The authors have, however, placed their “persons’ correctly on the map it’s just the numbers for each division that is incorrect. Strange.

In St. Vincent’s cemetery, on the other hand, the authors failed to use the official division layout. There are online resources here that will serve the visitor much better here.

But it is in Pere Lachaise cemetery that the largest number of errors appeared (all page references from the 1986 edition).

Division 1: (p. 10) They list Gustave Froment and Louis Lemaire; yet they don’t seem to be there. In fact they mention that Lemaire has a pyramid resembling the one on the $1 bill and there is no pyramid in division 1 (with the exception of the “Machado de Gama”).

Division 3: (p. 10) The authors refer to

Marie Lenormand when it should in fact be

Mademoiselle Lenormand (small point I know).

Division 6: (p. 15) They describe the tomb of Ferdinand de Lesseps (builder of the Suez canal) as “pyramid-shaped”. See if you think it looks like a pyramid. Send me a note and I’ll send you a photo of the tomb.

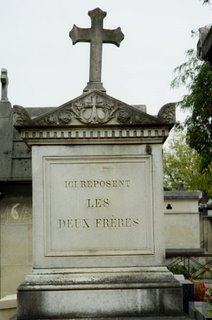

Page 24: They have a cool little photo here, which I assume they took, but I no idea where they took it: in Pere Lachaise, in Paris where?

Division 12: (p. 28) Serious problem here. The tomb they describe as belonging to Charles Lafont, the one with a man reclining holding a woman’s face is in his hands, which is across from Talma, actually belongs to Frederick Arbelot and is in division 11, not 12. Lafont is indeed in div. 12 but the other direction from Talma, and closer to Gericault.

Division 12: (p. 30) As already noted the photo of Gericault is reversed.

Division 18: (p. 36) The authors have placed Kellermann in 18 when in fact he belongs in div. 30. In fairness the delineation between the two divisions is confusing.

Division 19: (p. 37) They have placed Dr. Joseph Guillotin (yes

that Guillotin) here, near Dr. Hahnemann although there is no other source reporting his burial in this division. Only the “Friends of Pere Lachaise” website lists him as in fact in a long-abandoned tomb in division 7. Take your pick. Here again is an example of the problem that can result from authors not locating everyone on the map.

Division 31: (p. 48) Charles de Talleyrand-Perigord. The authors claim he has his own area all by himself – but I’m at a loss to know what they mean by “area”. There is a very large mausoleum located in division 31 which fits the spot on their tour map. The problem is that there are no markings on the mausoleum to denote Talleyrand or Perigord or anyone else for that matter. Furthermore, while the “Editions Metropolitain” map does list one Alexandre de Talleyrand-Perigord no other source mentions this burial. Not even the official cemetery map lists a Talleyrand buried in the cemetery, let alone in div. 31. Moreover, Beyern claims that Charles is buried at his chateau at Valencay in the Loire valley.

Division 54: (p. 61) It is

Charles not

Auguste de Morny.

Division 67: (p. 66) In regards to the story about Marie Walewska’s “hand” on display, inside the locked mausoleum, it is in fact her

heart not her hand which is buried in the tomb with her second husband, the Comte D’Orano. Her remains were sent back to Poland. In any case the authors failed to mention that her son, Alexandre Walewski (different spelling from his mother Marie) and the son of Napoleon I is buried in division 66.

Division 71: (p. 68) Regarding the spectacular story about balloonists Croce-Spinelli and Sivel, the authors fail to mention that the survivor of that ill-fated trip aboard the

Zenith, and who would go on to become quite famous in the world of high-altitude ballooning, Gaston Tissandier, is buried in division 27.

Division 87: (p. 75) The Columbarium is in fact not a crematorium (a separate structure altogether) but the place where the urns of ashes are located in niches specifically designed for that purpose. Since there are tens of thousands of niches in the Columbarium in Pere Lachaise the visitor must have the niche number or you will simply never find a specific individual. Sadly the authors only locate Isadora Duncan by number – although they do mention the pair of holding hands which is quite nice.

In any case the “Edition Metropolitain”map of Pere Lachaise can provide the visitor with the numbers for diva Maria Callas (16258), even though her ashes were in fact spread on the Aegean Sea, and for American author Richard Wright (848), jazz musician Stephane Grappelli (417) and a number of other well-known internationally known figures.

Certainly much of the Culbertson and Randall book is true, accurate, enlightening and entertaining. But the existence of so many errors and inattention to detail is nevertheless disturbing.