|

| 1840 Marty |

Sunday, May 03, 2015

Sunday, April 26, 2015

Sunday, April 19, 2015

Damage from aerial bombardment, World War 1

Damage to one of the cemeteries in Paris (probably Pere-Lachaise) as a result of a raid by German Gotha bombers in 1918.

Sunday, April 12, 2015

Sunday, April 05, 2015

Sunday, March 29, 2015

Saturday, March 28, 2015

The Paris Cemeteries website has a brand new look!

That's right, it's all brand new for 2015! You can see the redesign and updated information by visiting www.pariscemeteries.com.

|

| Père-Lachaise, c. 1815 reportedly by Courvoisier |

Sunday, March 22, 2015

Sunday, March 15, 2015

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

Pariscemeteries dot com has a new look!

Just a quick note to let you all know that my website, pariscemeteries dot com, has a brand new look. Just in case you're looking to stroll around . . .

Sunday, March 08, 2015

Sunday, March 01, 2015

Saturday, February 28, 2015

"A Woman's First Impressions of Europe," by Mrs. E. A. Forbes, 1863

["A Woman's First Impressions of Europe," by Mrs. E. A. Forbes, 1863]

Oct. 31. Visited Pere la Chaise, which, apart from the fact of its having been the first city cemetery beyond the churchyard burial places in the midst of the population, and its affording a noble view of Paris, possesses less interest than most cemeteries. The largest and most elaborate of the monuments is that of the Russian princess Demidoff; the one most worthy of a pilgrimage is the small temple, where lie side by side, unworthy conjunction, the effigies of Abelard and the unhappy Heloise.

Most of the monuments consist of small chapels, like boxes, in close contiguity, within which are hung garlands of immortelles, and sometimes of beads. Sometimes beautiful natural flowers stand in pots upon the little altar, and more frequently bouquets of artificial flowers supply their place. The French taste is, for many reasons, more successful in behalf of the living than of the dead, and the cemetery is a stiff one.

The most touching of all the resting places, to me, was a small plot, enclosed by an iron railing, with a hedge - without monument or inscription. By careful inspection one finds, rudely scratched upon the gate, as if by the point of a nail-Ney. It is a text for a volume of sermons.

We looked into the Jews' burial ground, which seems beautifully kept, with a quiet, un-Frenchy seclusion-the monument of Rachel is near its entrance. We saw the tombs of various French authors, and the statue of Casimir Perier, but found an hour or two in the streets of the necropolis a sufficient type of the whole.

Oct. 31. Visited Pere la Chaise, which, apart from the fact of its having been the first city cemetery beyond the churchyard burial places in the midst of the population, and its affording a noble view of Paris, possesses less interest than most cemeteries. The largest and most elaborate of the monuments is that of the Russian princess Demidoff; the one most worthy of a pilgrimage is the small temple, where lie side by side, unworthy conjunction, the effigies of Abelard and the unhappy Heloise.

Most of the monuments consist of small chapels, like boxes, in close contiguity, within which are hung garlands of immortelles, and sometimes of beads. Sometimes beautiful natural flowers stand in pots upon the little altar, and more frequently bouquets of artificial flowers supply their place. The French taste is, for many reasons, more successful in behalf of the living than of the dead, and the cemetery is a stiff one.

The most touching of all the resting places, to me, was a small plot, enclosed by an iron railing, with a hedge - without monument or inscription. By careful inspection one finds, rudely scratched upon the gate, as if by the point of a nail-Ney. It is a text for a volume of sermons.

We looked into the Jews' burial ground, which seems beautifully kept, with a quiet, un-Frenchy seclusion-the monument of Rachel is near its entrance. We saw the tombs of various French authors, and the statue of Casimir Perier, but found an hour or two in the streets of the necropolis a sufficient type of the whole.

Sunday, February 22, 2015

Saturday, February 21, 2015

Pere-Lachaise described by John Adolphus, 1820

[Emily Henderson, Recollections of the Public Career and Private We of the Late John Adolphus, London, 1871, pp. 118-119]

"We all went this morning to the Cimetiere of Pere la Chaise, the celebrated burial ground, where everything ancient and modern that can be laid hands on is brought together for a. show. The ground is said to contain 80 acres, and is on the ascent of a hill, so that tombs above tombs rise in ranks, and as they are mostly planted with firs, shrubs, and flowers, the effect of these mixed with mausoleums, columns, and -other memorials of death, is exceedingly pretty; and if the sole business of those who inter the dead is to make their burial place look pretty, and to allure people to it as a gazing place, the French have indeed succeeded to a miracle.

"When I walk through the aisles of Westminster Abbey, of St. Paul's, of Canterbury, and other cathedrals and ancient churches, and see the structures raised in honour of the illustrious dead; when I read their histories, recorded in an imperishable language, and see their effigies sculptured in an attitude of devotion, or surrounded by some of the host of heaven, my heart warms with the recollection of their famous acts, and melts in sympathy with those pious friends who, in commemorating their worth, have not forgotten to express the hope of their everlasting welfare in a better world. Even when in a more humble churchyard I perceive the frail memorials raised by unlettered humanity, the rhyme uncouth, the 'shapeless sculpture,' and the' many a holy text,' are so apposite to the situation that I feel as a son towards the aged 'forefathers of the hamlet,' and as a brother or parent toward the young. They are buried as a family; the almost universal description is 'of this parish,' and they all profess the hope of meeting again in a joyful resurrection. But in this strange raree-show of death the tomb of Abelard greets you here, those of Boileau, Moliere, and Racine there. Here a warrior who fought at Fontenoy, and continued fighting till 1793; there an insignificant tomb, guarded with heavy chains, denotes the resting place of a shopkeeper who died worth a great deal of money. All these concur in a general contempt of religion, for not one in a hundred condescends to say 'resurgam,' but as many as have any wit or fancy try to surprise you into a stare, or tickle you into a laugh. A lady inscribes on a tomb, 'To my best friend, my husband.' Another,' Alexander to his mother.' Alexander! What Alexander-the Great? the Coppersmith? or who? Find it out, says the tombstone. Another commemorates, ' Zenobia and Zoe.' 'Pray, sir,' said I to a French artisan, who had asked me a question about the inscription, 'were these young ladies your daughters or mine?' The man stared as if struck with a new idea. ' Why to be sure,' he said, ' they ought to have put their nom de fami1le.'

"Many of the tombs are very pretty, and some yet unfinished seemed well suited to their purpose, and to promise long duration, but the general air of the place was to me heathenish or worse. I could not help thinking that if Gobet could again be Bishop of Paris, and Hebert, Chaumette, and the rest of the Cordeliers again succeed in abolishing the belief in God, the proprietors of this cemetery would have little to do beside inscribing on the portal, ' Death is an eternal sleep,' to bring it quite to the level of the day.

"Paris is seen to great advantage from Pere la Chaise, but no distant view of it affords much pleasure. From this spot its white walls, standing in an arid plain, form a continuation of the burying-place, and so require little aid of fancy to blend the mansions of the living with the receptacles of the dead.

"We all went this morning to the Cimetiere of Pere la Chaise, the celebrated burial ground, where everything ancient and modern that can be laid hands on is brought together for a. show. The ground is said to contain 80 acres, and is on the ascent of a hill, so that tombs above tombs rise in ranks, and as they are mostly planted with firs, shrubs, and flowers, the effect of these mixed with mausoleums, columns, and -other memorials of death, is exceedingly pretty; and if the sole business of those who inter the dead is to make their burial place look pretty, and to allure people to it as a gazing place, the French have indeed succeeded to a miracle.

"When I walk through the aisles of Westminster Abbey, of St. Paul's, of Canterbury, and other cathedrals and ancient churches, and see the structures raised in honour of the illustrious dead; when I read their histories, recorded in an imperishable language, and see their effigies sculptured in an attitude of devotion, or surrounded by some of the host of heaven, my heart warms with the recollection of their famous acts, and melts in sympathy with those pious friends who, in commemorating their worth, have not forgotten to express the hope of their everlasting welfare in a better world. Even when in a more humble churchyard I perceive the frail memorials raised by unlettered humanity, the rhyme uncouth, the 'shapeless sculpture,' and the' many a holy text,' are so apposite to the situation that I feel as a son towards the aged 'forefathers of the hamlet,' and as a brother or parent toward the young. They are buried as a family; the almost universal description is 'of this parish,' and they all profess the hope of meeting again in a joyful resurrection. But in this strange raree-show of death the tomb of Abelard greets you here, those of Boileau, Moliere, and Racine there. Here a warrior who fought at Fontenoy, and continued fighting till 1793; there an insignificant tomb, guarded with heavy chains, denotes the resting place of a shopkeeper who died worth a great deal of money. All these concur in a general contempt of religion, for not one in a hundred condescends to say 'resurgam,' but as many as have any wit or fancy try to surprise you into a stare, or tickle you into a laugh. A lady inscribes on a tomb, 'To my best friend, my husband.' Another,' Alexander to his mother.' Alexander! What Alexander-the Great? the Coppersmith? or who? Find it out, says the tombstone. Another commemorates, ' Zenobia and Zoe.' 'Pray, sir,' said I to a French artisan, who had asked me a question about the inscription, 'were these young ladies your daughters or mine?' The man stared as if struck with a new idea. ' Why to be sure,' he said, ' they ought to have put their nom de fami1le.'

"Many of the tombs are very pretty, and some yet unfinished seemed well suited to their purpose, and to promise long duration, but the general air of the place was to me heathenish or worse. I could not help thinking that if Gobet could again be Bishop of Paris, and Hebert, Chaumette, and the rest of the Cordeliers again succeed in abolishing the belief in God, the proprietors of this cemetery would have little to do beside inscribing on the portal, ' Death is an eternal sleep,' to bring it quite to the level of the day.

"Paris is seen to great advantage from Pere la Chaise, but no distant view of it affords much pleasure. From this spot its white walls, standing in an arid plain, form a continuation of the burying-place, and so require little aid of fancy to blend the mansions of the living with the receptacles of the dead.

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

"Père Lachaise. Rain" by Robert Steadman

Sit back, listen to this quiet piano and imagine you're strolling the chemins of Pere-Lachaise, alone, at peace.

Sunday, February 15, 2015

Saturday, February 14, 2015

Pere-Lachaise described by Sir Jonah Barrington, 1827

["PERE LA CHAISE," in Personal Sketches of His Own Times, volume II, 1827, by Sir Jonah Barrington, pp. 432-35]

The visitor of Paris will find it both curious and interesting to contrast with these another receptacle for the dead - the cemetery of Pere la Chaise. It is strange that there should exist amongst the same people, in the same city, and almost in the same vicinity - two Golgothas in their nature so utterly dissimilar and repugnant from each other.

The soft and beautiful features of landscape which characterise Pere la Chaise are scarcely describable: so harmoniously are they blended together,-so sacred does the spot appear to quiet contemplation and hopeful repose,that it seems almost profanation to attempt to submit its charms in detail before the reader's eye. All in fact that I had ever read about it fell, as in the case of the catacombs - ("alike, but ah, how different!") far short of the reality.

I have wandered whole mornings together over its winding paths and venerable avenues. Here are no "ninety steps" of descent to gloom and horror: on the contrary, a gradual ascent leads to the cemetery of Pere la Chaise, and to its enchanting summit, on every side shaded by brilliant evergreens. The straight lofty cypress and spreading cedar uplift themselves around, and the arbutus exposing all its treasure of deceptive berries. In lieu of the damp mouldering scent exhaled by three millions of human skeletons, we are presented with the fragrant perfume of jessamines and of myrtles-of violet beds or variegated flower-plats decked out by the ministering hand of love or duty; as if benignant nature had spread her most splendid carpet to cover, conceal, and render alluring even the abode of death.

Whichever way we turn, the labours of art combine with the luxuriance of vegetation to raise in the mind new reflections: marble, in all its varieties of shade and grain, is wrought by the hand of man into numerous bewitching shapes; whilst one of the most brilliant and cheerful cities in the universe seems to lie, with its wooded boulevards, gilded domes, palaces, gardens, and glittering waters, just beneath our feet. One sepulchre, alone, of a decidedly mournful character, attracted my notice :-a large and solid mausoleum, buried amidst gloomy yews and low drooping willows; and this looked only like a patch on the face of loveliness. Pere la Chaise presents a solitary instance of the abode of the dead ever interesting me in an agreeable way.

I will not remark on the well-known tomb of Abelard and Eloisa: a hundred pens have anticipated me in most of the observations I should be inclined to make respecting that celebrated couple. The most obvious circumstance in their "sad story" always struck me as being -- that he turned priest when he was good for nothing else, and she became "quite correct" when opportunities for the reverse began to slacken. They no doubt were properly qualified to make very respectable saints: but since they took care previously to have their fling, I cannot say much for their morality.

I am not sure that a burial-place similar to Pere la Chaise would be admired in England: it is almost of too picturesque and sentimental a character. The humbler orders of the English people are too coarse to appreciate the peculiar feeling such a cemetery is calculated to excite: the higher orders too licentious; the trading classes too avaricious. The plum-holder of the city would very honestly and frankly "d--n all your nonsensical sentiment!" I heard one of these gentlemen, last year, declare that what poets and such-like called sentiment was neither more nor less than deadly poison to the Protestant religion!

The visitor of Paris will find it both curious and interesting to contrast with these another receptacle for the dead - the cemetery of Pere la Chaise. It is strange that there should exist amongst the same people, in the same city, and almost in the same vicinity - two Golgothas in their nature so utterly dissimilar and repugnant from each other.

The soft and beautiful features of landscape which characterise Pere la Chaise are scarcely describable: so harmoniously are they blended together,-so sacred does the spot appear to quiet contemplation and hopeful repose,that it seems almost profanation to attempt to submit its charms in detail before the reader's eye. All in fact that I had ever read about it fell, as in the case of the catacombs - ("alike, but ah, how different!") far short of the reality.

I have wandered whole mornings together over its winding paths and venerable avenues. Here are no "ninety steps" of descent to gloom and horror: on the contrary, a gradual ascent leads to the cemetery of Pere la Chaise, and to its enchanting summit, on every side shaded by brilliant evergreens. The straight lofty cypress and spreading cedar uplift themselves around, and the arbutus exposing all its treasure of deceptive berries. In lieu of the damp mouldering scent exhaled by three millions of human skeletons, we are presented with the fragrant perfume of jessamines and of myrtles-of violet beds or variegated flower-plats decked out by the ministering hand of love or duty; as if benignant nature had spread her most splendid carpet to cover, conceal, and render alluring even the abode of death.

Whichever way we turn, the labours of art combine with the luxuriance of vegetation to raise in the mind new reflections: marble, in all its varieties of shade and grain, is wrought by the hand of man into numerous bewitching shapes; whilst one of the most brilliant and cheerful cities in the universe seems to lie, with its wooded boulevards, gilded domes, palaces, gardens, and glittering waters, just beneath our feet. One sepulchre, alone, of a decidedly mournful character, attracted my notice :-a large and solid mausoleum, buried amidst gloomy yews and low drooping willows; and this looked only like a patch on the face of loveliness. Pere la Chaise presents a solitary instance of the abode of the dead ever interesting me in an agreeable way.

I will not remark on the well-known tomb of Abelard and Eloisa: a hundred pens have anticipated me in most of the observations I should be inclined to make respecting that celebrated couple. The most obvious circumstance in their "sad story" always struck me as being -- that he turned priest when he was good for nothing else, and she became "quite correct" when opportunities for the reverse began to slacken. They no doubt were properly qualified to make very respectable saints: but since they took care previously to have their fling, I cannot say much for their morality.

I am not sure that a burial-place similar to Pere la Chaise would be admired in England: it is almost of too picturesque and sentimental a character. The humbler orders of the English people are too coarse to appreciate the peculiar feeling such a cemetery is calculated to excite: the higher orders too licentious; the trading classes too avaricious. The plum-holder of the city would very honestly and frankly "d--n all your nonsensical sentiment!" I heard one of these gentlemen, last year, declare that what poets and such-like called sentiment was neither more nor less than deadly poison to the Protestant religion!

Wednesday, February 11, 2015

Sunday, February 08, 2015

Saturday, February 07, 2015

The Cemetery of Pere La Chaise, in The New Monthly, 1825

["The Cemetery of Pere La Chaise," 1822 The New Monthly, pp. 155-59]

I am half disposed to admit the assertion of a lively authoress, that the French are a grave people, and absolutely determined upon contradicting the received opinion in England, that in the volatility of their character their sympathies, however easily excited, are generally evanescent; and that the claims of kindred or friendship, so far from awakening any permanent sensibility, are quickly superseded by the paramount dominion of frivolity and amusement. Let any man who is laboring under this mistaken impression pay a visit to the Cemetery of Pere La Chaise; and if he do not hate France more than falsehood, he will admit that in the precincts of this beautiful and affecting spot there is not only a more striking assemblage of tasteful decoration and appropriate monumental sculpture, but more pervading evidences of deep, lingering, heart-rending affection for the dead than could be paralleled in England or any other country of Europe. The tombs elsewhere seem to be monuments of oblivion, not remembrance – they designate spots to be avoided, not visited, unless by the idle curiosity of strangers; here they seem built up with the heart as well as with the hands; -- they are hallowed by the frequent presence of sorrowing survivors, who, by various devices of ingenious and elegant offerings, still testify their grief and their respect for the departed, and keep up by these pious visitings a sort of holy communion between the living and the dead.

Never, never shall I forget the solemn, yet sweet and soothing emotions that thrilled my bosom at the first visit to Pere La Chaise. Women were in attendance as we approached the gate, offering for sale elegant crowns, crosses, and wreaths of orange blossom, xereanthemum, amaranth, and other everlasting flowers, which the mourning relatives and friends are accustomed to suspend upon the monument, or throw down upon the grave, or entwine among the shrubs with which every enclosure is decorated.

Congratulating myself that I had no such melancholy office to perform, I passed into this vast sanctuary of the dead, and found myself in a variegated and wide-spreading garden, consisting of hill and dale, redolent with flowers, and thickly planted with luxuriant shrubs and trees, from the midst of which monumental stones, columns, obelisks, pyramids, and temples shot up in such profusion that I was undecided which path to explore first, and stood some time in silent contemplation of the whole scene, which occupies a space of from sixty to eighty acres. A lofty Gothic monument on the right first claimed my attention, and on approaching it I found that it contained the tomb in which are the ashes of Abelard and Eloiosa, united at last in death, but even then denied that rest and repose to which they were strangers in their unhappy and passionate lives. Interred, after various removals, at Soissons, in the year 1120, they were transported in the year eight of the Republic from Chalons sur Saone to the Museum of French Monuments at Paris, and thence to the romantic spot which they at present occupy. We learn from the inscription, that with all his talents Abelard could not comprehend the doctrine of the Trinity, and on this account incurred the censure of [156] contemporary hierarchs. Subsequently, however, he seems to have seen the wisdom of a more accommodating faith; and having evinced his orthodoxy by the irrefutable argument of causing three figures to be sculptured upon one stone, which is still visible, being let into the side of his tomb, he was restored to confidence and protection of the church. I have seen at Paris the dilapidated house in which he is stated to have resided; and now to be standing above the very dust which once contributed to form the fine intellect and throbbing hearts of these celebrated lovers, seemed to be an annihilation of intervening centuries, throwing the mind back to that remote period when Eliosa from the “deep solitudes and awful cells” of her convent edited those love—breathing epistles which have spread through the world the fame of her unhappy attachment.

Quitting this interesting spot, a wilderness of little enclosures presented itself, almost every one profusely planted with flowers, and overshadowed by poplar, cypress, weeping willow, and arbor vitae, interspersed among the flowering shrubs and fruit trees; for the ground, before its present appropriation had been laid out as a pleasure garden. Many of the tombs were provided with a watering-pot for the refreshment of the flowers, and the majority had a stone seat for the accommodation of those who came hither to indulge in melancholy retrospection, as they stationed themselves upon the grave in which their affections were deposited. Here and there the sufferers from filial, parental, or conjugal deprivation, were seem trimming the foliage or flowers that sprung up from the remains of their kindred flesh, and as they handled the shrubs, whose roots struck down into the very grave, one could almost image that the dead stretched forth into their leafy arms from the earth to embrace once more those whom they had so fondly encircled when alive. In many instances, however, it must be confessed that this pious duty was deputed to the keepers of the ground, who for a small stipend maintained the tombs in a perpetual greenness. Some contented themselves with hanging a funeral garland on the monuments of their friends, by the number and freshness of which tributes we were enabled to judge, in some degree, of the merits of the deceased, and of the recency with which sad bosoms and glistening eyes had occupied the spot on which then stood. Some were blooming all over with these flowery offerings, while others with a single forlorn and withered chaplet, or absolutely bare, showed that their mouldering tenants had left no friends behind; or that time had wrought his usual effect, and either brought them to the same appointed house, or “steeped their senses in forgetfulness.”

In ascending the hill extensive family vaults are seen, excavated in its side in the style of the ancients, with numerous recesses for coffins, the whole enclosed by bronze gates of exquisite taste and workmanship, through which might be seen the chairs for those who wish to shut themselves up and meditate in the sepulcher which they are permanently to occupy; while the yellow wreath upon the ground, or coffin, pointed out the latest occupant of the chamber of death. Some well-known name was perpetually presenting itself to our notice. In one place we encountered the tomb of the unfortunate Laboydere, who was the first to join Napoleon when he advanced to Grenoble in 1815, and expiated his offence with his life. The spot in which the hapless Ney was deposited was shown to us, but his monument [157] has been removed. A lofty and elegant pyramid on the height bore the name of the celebrated Massena; and as we roamed about, we trod over the remains of republicans, royalists, marshals, demagogues, liberals, ultras, and many of the victors and victims of the Revolution, whose exploits and sufferings have filled our gazettes, and been familiar in our mouths for the last twenty or thirty years.

A few steps more brought us to the summit of the hill, commanding a noble view of Paris, the innumerable white buildings of which stood out with a panoramic and lucid sharpness in the deep blue of a cloudless sky, not a single wreath of smoke dimming the clearness of the view. Nothing was seen to move – a dead silence reigned around – the whole scene resembled a bright and tranquil painting.

On the highest point of the whole cemetery, under the shade of eight lime trees planted in a square, is the tomb of Frederic Mestezart, a Protestant pastor of the Church of Geneva. A French writer well observes, on the occasion of this tomb, raised in the midst of the graves of Catholics, and in the former property of one of the most cruel persecutors of Protestantism, “O the power of time, and of the revolutions which it brings in its train! A minister of Calvin reposes not far from the Charenton where the reformed religion saw its temple demolished and its preacher proscribed! He reposes in that ground where a bigoted Jesuit loved to meditate on his plans of intolerance and persecution!”

Not far from this spot is the tomb of the well-known authoress Madame Cottin, and monuments have also been lately erected to the memory of Lafontaine and Moliere. A low pyramid is the appropriate sepulcher of Volney; and at the extremity of a walk of trees, surrounded by a little garden, is the equally well adapted monument of Delille, the poet of the Gardens. Mentelle and Fourcroy repose at a little distance and in the same vicinity, beneath a square tomb of white marble, decorated with a lyre, are deposited the remains of Gretry, the celebrated composer, whose bust I had the day before seen in the garden of the Hermitage art Montmorency, once occupied by Rousseau. How refreshing to turn from the costly and luxurious memorials of many who had been the torments and scourges of their time, to these classic shades, where sleep the benefactors of the world, men who have enlightened it by their wisdom, animated it by their gaiety, or soothed it by their delightful harmonies!

Amid the tombs upon the heights a low enclosure, arched over at top to preserve it from the weather, but fenced at the sides with open wire-work, through which we observed that the whole interior surface was carefully overspread with moss, and strewed with fresh gathered white flowers, which also expanded their fragrance from vases of white porcelain, the whole arranged with exquisite neatness and care. There was no name or record but the following simple and pathetic inscription: “Fille Cherie – avec toi mes beaux jours sont passes! 5 Juin, 1819.” Above two years had elapsed since the erection of this tomb, yet whenever I subsequently visited it, which I sometimes did at an early hour, the wakeful and unwearied solicitude of maternal regret had preceded me; the moss was newly laid, the flowers appeared to be just plucked, the vases shone with unsullied whiteness, as if even the dew had been carefully wiped off. How keen and intense must have [158] been that affection which could so long survive its object, and gather fresh force even from the energy of despair!

An inscription to the memory of Eleanor MacGowan, a Scotch-woman recalled to mind the touching lines of Pope – “by foreign hands, etc.” but though we might admire the characteristic nationality, we could hardly applaud the taste which had planted this grave, as well as some others of her countrymen, with thistles. English names often startled us as we walked through the alleys of tomb-stones; and it as gratifying to find that even from these, the coarse and clumsy, though established emblems of the death’s head and marrow bones had been discarded. Obtuse, indeed must be those faculties which need such repulsive bone-writing to explain to them the perishableness of humanity.

We nowhere encountered any of the miserable doggerel which defaces our graves in England, under the abused name of poetry; and, in fact, poetic inscriptions of any sort were extremely rare. Some may assign this to the want of poetical genius in the French, but it might be certainly more charitable, and possibly more just, to attribute it to the sincerity of their regrets; for I doubt whether the lacerated bosom, in the first burst of its grief, has ever any disposition to dally with the Muses. A softened heart may seek solace in such effusions, but not an agonized one. Some rhyming epitaphs were, however visible. Under the name of the well known Regnault de St. Jean d’Angely these lines were inscribed.

“Francois, de son dernier soupir Il a salue la patrie; Un meme jour a vu finir Ses maux, son exil, et sa vie.”

And a very handsome monument to the memory of an artist, in bronze and gold, named Ravrio, informs us that he was the author also of numerous fugitive pieces, to prevent his following which into oblivion, his bust, well executed in bronze, surmounts his tomb; and the following verses give us a little insight into his character.

“Un fils d’Anacreon a finis a carriere, Il est dans ce tombeau pour jamais endormi, Les enfans des beaux arts sont prives de leur frère, Les malheaureux ont perdu leur ami.”

The practice of affixing busts to tombs seems worthy of more general adoption – it identifies and individualizes the deceased and thus creates a more definable object for our sympathies. Perhaps the miniatures which we occasionally saw let into the tombstones and glazed over, attained this point more effectually, as the contrast between the bright eye and the blooming cheek above, and the fleshless skeleton below, was rendered doubly impressive. Not only is the doggerel of the English church-yard banished from Pere La Chaise, but it is undegraded by the bad spelling and ungrammatical construction which with us are so apt to awaken ludicrous ideas, where none but solemn impressions should be felt. The order by which all lapidary inscriptions must be submitted to previous inspection, though savouring somewhat of arbitrary regulation, is perhaps necessary in the present excited state of political feeling, and is doubtless the main cause of the general [159] propriety and decorum by which they are distinguished. The whole management of the place appears to be admirably conducted – decency and good order universally prevailed – not a stone scribbled over. It was impossible to avoid drawing painful comparisons between the state of the plainest tombs here, and the most elaborate in Westminster Abbey, defaced and desecrated as many of the latter are by the empty-headed puppies of the adjoining school, and the brutal violations of an uncivilized rabble. This sacred respect for the works of art is not peculiar to the Cemetery of Pere La Chaise, nor solely due to the vigilance of the police, for in the innumerable statues and sculptures with which Paris and its neighborhood abound many scattered about in solitary walks and gardens at the mercy of the public, I have never observed the smallest mutilation, nor nay indecorous scribbling. The lowest Frenchman has been familiarized with works of art until he has learnt to take a pride in them, and to this extent at least has verified the old adage, that such a feeling “emollit mores nec sinit esse feros.”

As I stood upon the hill, I saw a funeral procession slowly winding amid the trees and avenues below. Its distant effect was impressive, but, as it approached, it appeared to be strikingly deficient in that well-appointed and consistent solemnity by which the same ceremony is uniformly distinguished in England. The hearse was dirty and shabby, the mourning coaches as bad, the horses and harness worse; the coachmen in their rusty coats and cocked hats seemed to be a compound of paupers and old clothesmen; the dress of the priests had an appearance at once mean and ludicrous; the coffin was an unpainted deal box; the grave was hardly four feet deep, and the whole service was performed in a careless and unimpressive manner. Yet this was a funeral of a substantial tradesman, followed by a respectable train of mourners. Here was all the external observance, perhaps, that reason requires; but where our associations have been made conversant with a more scrupulous and dignified treatment, it is difficult to reconcile ourselves to such a slovenly mode of interment, although it may be the established system of the country. All the funerals here are in the hands of a company, who, for the privilege of burying the rich at fixed prices, contract to inhume all the poor for nothing. It is hardly to be supposed, that in such a multiplicity of tomb there are not some offensive to good taste. Many are gaudy and fantastical, dressed up with paltry figures of the Virgin and Child, and those tin and tinsel decorations which the rich in faith and poor pocket are apt to set up in Roman Catholic countries – but the generality are of a much nobler order, and I defy any candid traveler to spend a morning in the Cemetery of Pere La Chaise without feeling a higher respect for the French character, and forming a more pleasing estimate of human nature in general.

I am half disposed to admit the assertion of a lively authoress, that the French are a grave people, and absolutely determined upon contradicting the received opinion in England, that in the volatility of their character their sympathies, however easily excited, are generally evanescent; and that the claims of kindred or friendship, so far from awakening any permanent sensibility, are quickly superseded by the paramount dominion of frivolity and amusement. Let any man who is laboring under this mistaken impression pay a visit to the Cemetery of Pere La Chaise; and if he do not hate France more than falsehood, he will admit that in the precincts of this beautiful and affecting spot there is not only a more striking assemblage of tasteful decoration and appropriate monumental sculpture, but more pervading evidences of deep, lingering, heart-rending affection for the dead than could be paralleled in England or any other country of Europe. The tombs elsewhere seem to be monuments of oblivion, not remembrance – they designate spots to be avoided, not visited, unless by the idle curiosity of strangers; here they seem built up with the heart as well as with the hands; -- they are hallowed by the frequent presence of sorrowing survivors, who, by various devices of ingenious and elegant offerings, still testify their grief and their respect for the departed, and keep up by these pious visitings a sort of holy communion between the living and the dead.

Never, never shall I forget the solemn, yet sweet and soothing emotions that thrilled my bosom at the first visit to Pere La Chaise. Women were in attendance as we approached the gate, offering for sale elegant crowns, crosses, and wreaths of orange blossom, xereanthemum, amaranth, and other everlasting flowers, which the mourning relatives and friends are accustomed to suspend upon the monument, or throw down upon the grave, or entwine among the shrubs with which every enclosure is decorated.

Congratulating myself that I had no such melancholy office to perform, I passed into this vast sanctuary of the dead, and found myself in a variegated and wide-spreading garden, consisting of hill and dale, redolent with flowers, and thickly planted with luxuriant shrubs and trees, from the midst of which monumental stones, columns, obelisks, pyramids, and temples shot up in such profusion that I was undecided which path to explore first, and stood some time in silent contemplation of the whole scene, which occupies a space of from sixty to eighty acres. A lofty Gothic monument on the right first claimed my attention, and on approaching it I found that it contained the tomb in which are the ashes of Abelard and Eloiosa, united at last in death, but even then denied that rest and repose to which they were strangers in their unhappy and passionate lives. Interred, after various removals, at Soissons, in the year 1120, they were transported in the year eight of the Republic from Chalons sur Saone to the Museum of French Monuments at Paris, and thence to the romantic spot which they at present occupy. We learn from the inscription, that with all his talents Abelard could not comprehend the doctrine of the Trinity, and on this account incurred the censure of [156] contemporary hierarchs. Subsequently, however, he seems to have seen the wisdom of a more accommodating faith; and having evinced his orthodoxy by the irrefutable argument of causing three figures to be sculptured upon one stone, which is still visible, being let into the side of his tomb, he was restored to confidence and protection of the church. I have seen at Paris the dilapidated house in which he is stated to have resided; and now to be standing above the very dust which once contributed to form the fine intellect and throbbing hearts of these celebrated lovers, seemed to be an annihilation of intervening centuries, throwing the mind back to that remote period when Eliosa from the “deep solitudes and awful cells” of her convent edited those love—breathing epistles which have spread through the world the fame of her unhappy attachment.

Quitting this interesting spot, a wilderness of little enclosures presented itself, almost every one profusely planted with flowers, and overshadowed by poplar, cypress, weeping willow, and arbor vitae, interspersed among the flowering shrubs and fruit trees; for the ground, before its present appropriation had been laid out as a pleasure garden. Many of the tombs were provided with a watering-pot for the refreshment of the flowers, and the majority had a stone seat for the accommodation of those who came hither to indulge in melancholy retrospection, as they stationed themselves upon the grave in which their affections were deposited. Here and there the sufferers from filial, parental, or conjugal deprivation, were seem trimming the foliage or flowers that sprung up from the remains of their kindred flesh, and as they handled the shrubs, whose roots struck down into the very grave, one could almost image that the dead stretched forth into their leafy arms from the earth to embrace once more those whom they had so fondly encircled when alive. In many instances, however, it must be confessed that this pious duty was deputed to the keepers of the ground, who for a small stipend maintained the tombs in a perpetual greenness. Some contented themselves with hanging a funeral garland on the monuments of their friends, by the number and freshness of which tributes we were enabled to judge, in some degree, of the merits of the deceased, and of the recency with which sad bosoms and glistening eyes had occupied the spot on which then stood. Some were blooming all over with these flowery offerings, while others with a single forlorn and withered chaplet, or absolutely bare, showed that their mouldering tenants had left no friends behind; or that time had wrought his usual effect, and either brought them to the same appointed house, or “steeped their senses in forgetfulness.”

In ascending the hill extensive family vaults are seen, excavated in its side in the style of the ancients, with numerous recesses for coffins, the whole enclosed by bronze gates of exquisite taste and workmanship, through which might be seen the chairs for those who wish to shut themselves up and meditate in the sepulcher which they are permanently to occupy; while the yellow wreath upon the ground, or coffin, pointed out the latest occupant of the chamber of death. Some well-known name was perpetually presenting itself to our notice. In one place we encountered the tomb of the unfortunate Laboydere, who was the first to join Napoleon when he advanced to Grenoble in 1815, and expiated his offence with his life. The spot in which the hapless Ney was deposited was shown to us, but his monument [157] has been removed. A lofty and elegant pyramid on the height bore the name of the celebrated Massena; and as we roamed about, we trod over the remains of republicans, royalists, marshals, demagogues, liberals, ultras, and many of the victors and victims of the Revolution, whose exploits and sufferings have filled our gazettes, and been familiar in our mouths for the last twenty or thirty years.

A few steps more brought us to the summit of the hill, commanding a noble view of Paris, the innumerable white buildings of which stood out with a panoramic and lucid sharpness in the deep blue of a cloudless sky, not a single wreath of smoke dimming the clearness of the view. Nothing was seen to move – a dead silence reigned around – the whole scene resembled a bright and tranquil painting.

On the highest point of the whole cemetery, under the shade of eight lime trees planted in a square, is the tomb of Frederic Mestezart, a Protestant pastor of the Church of Geneva. A French writer well observes, on the occasion of this tomb, raised in the midst of the graves of Catholics, and in the former property of one of the most cruel persecutors of Protestantism, “O the power of time, and of the revolutions which it brings in its train! A minister of Calvin reposes not far from the Charenton where the reformed religion saw its temple demolished and its preacher proscribed! He reposes in that ground where a bigoted Jesuit loved to meditate on his plans of intolerance and persecution!”

Not far from this spot is the tomb of the well-known authoress Madame Cottin, and monuments have also been lately erected to the memory of Lafontaine and Moliere. A low pyramid is the appropriate sepulcher of Volney; and at the extremity of a walk of trees, surrounded by a little garden, is the equally well adapted monument of Delille, the poet of the Gardens. Mentelle and Fourcroy repose at a little distance and in the same vicinity, beneath a square tomb of white marble, decorated with a lyre, are deposited the remains of Gretry, the celebrated composer, whose bust I had the day before seen in the garden of the Hermitage art Montmorency, once occupied by Rousseau. How refreshing to turn from the costly and luxurious memorials of many who had been the torments and scourges of their time, to these classic shades, where sleep the benefactors of the world, men who have enlightened it by their wisdom, animated it by their gaiety, or soothed it by their delightful harmonies!

Amid the tombs upon the heights a low enclosure, arched over at top to preserve it from the weather, but fenced at the sides with open wire-work, through which we observed that the whole interior surface was carefully overspread with moss, and strewed with fresh gathered white flowers, which also expanded their fragrance from vases of white porcelain, the whole arranged with exquisite neatness and care. There was no name or record but the following simple and pathetic inscription: “Fille Cherie – avec toi mes beaux jours sont passes! 5 Juin, 1819.” Above two years had elapsed since the erection of this tomb, yet whenever I subsequently visited it, which I sometimes did at an early hour, the wakeful and unwearied solicitude of maternal regret had preceded me; the moss was newly laid, the flowers appeared to be just plucked, the vases shone with unsullied whiteness, as if even the dew had been carefully wiped off. How keen and intense must have [158] been that affection which could so long survive its object, and gather fresh force even from the energy of despair!

An inscription to the memory of Eleanor MacGowan, a Scotch-woman recalled to mind the touching lines of Pope – “by foreign hands, etc.” but though we might admire the characteristic nationality, we could hardly applaud the taste which had planted this grave, as well as some others of her countrymen, with thistles. English names often startled us as we walked through the alleys of tomb-stones; and it as gratifying to find that even from these, the coarse and clumsy, though established emblems of the death’s head and marrow bones had been discarded. Obtuse, indeed must be those faculties which need such repulsive bone-writing to explain to them the perishableness of humanity.

We nowhere encountered any of the miserable doggerel which defaces our graves in England, under the abused name of poetry; and, in fact, poetic inscriptions of any sort were extremely rare. Some may assign this to the want of poetical genius in the French, but it might be certainly more charitable, and possibly more just, to attribute it to the sincerity of their regrets; for I doubt whether the lacerated bosom, in the first burst of its grief, has ever any disposition to dally with the Muses. A softened heart may seek solace in such effusions, but not an agonized one. Some rhyming epitaphs were, however visible. Under the name of the well known Regnault de St. Jean d’Angely these lines were inscribed.

“Francois, de son dernier soupir Il a salue la patrie; Un meme jour a vu finir Ses maux, son exil, et sa vie.”

And a very handsome monument to the memory of an artist, in bronze and gold, named Ravrio, informs us that he was the author also of numerous fugitive pieces, to prevent his following which into oblivion, his bust, well executed in bronze, surmounts his tomb; and the following verses give us a little insight into his character.

“Un fils d’Anacreon a finis a carriere, Il est dans ce tombeau pour jamais endormi, Les enfans des beaux arts sont prives de leur frère, Les malheaureux ont perdu leur ami.”

The practice of affixing busts to tombs seems worthy of more general adoption – it identifies and individualizes the deceased and thus creates a more definable object for our sympathies. Perhaps the miniatures which we occasionally saw let into the tombstones and glazed over, attained this point more effectually, as the contrast between the bright eye and the blooming cheek above, and the fleshless skeleton below, was rendered doubly impressive. Not only is the doggerel of the English church-yard banished from Pere La Chaise, but it is undegraded by the bad spelling and ungrammatical construction which with us are so apt to awaken ludicrous ideas, where none but solemn impressions should be felt. The order by which all lapidary inscriptions must be submitted to previous inspection, though savouring somewhat of arbitrary regulation, is perhaps necessary in the present excited state of political feeling, and is doubtless the main cause of the general [159] propriety and decorum by which they are distinguished. The whole management of the place appears to be admirably conducted – decency and good order universally prevailed – not a stone scribbled over. It was impossible to avoid drawing painful comparisons between the state of the plainest tombs here, and the most elaborate in Westminster Abbey, defaced and desecrated as many of the latter are by the empty-headed puppies of the adjoining school, and the brutal violations of an uncivilized rabble. This sacred respect for the works of art is not peculiar to the Cemetery of Pere La Chaise, nor solely due to the vigilance of the police, for in the innumerable statues and sculptures with which Paris and its neighborhood abound many scattered about in solitary walks and gardens at the mercy of the public, I have never observed the smallest mutilation, nor nay indecorous scribbling. The lowest Frenchman has been familiarized with works of art until he has learnt to take a pride in them, and to this extent at least has verified the old adage, that such a feeling “emollit mores nec sinit esse feros.”

As I stood upon the hill, I saw a funeral procession slowly winding amid the trees and avenues below. Its distant effect was impressive, but, as it approached, it appeared to be strikingly deficient in that well-appointed and consistent solemnity by which the same ceremony is uniformly distinguished in England. The hearse was dirty and shabby, the mourning coaches as bad, the horses and harness worse; the coachmen in their rusty coats and cocked hats seemed to be a compound of paupers and old clothesmen; the dress of the priests had an appearance at once mean and ludicrous; the coffin was an unpainted deal box; the grave was hardly four feet deep, and the whole service was performed in a careless and unimpressive manner. Yet this was a funeral of a substantial tradesman, followed by a respectable train of mourners. Here was all the external observance, perhaps, that reason requires; but where our associations have been made conversant with a more scrupulous and dignified treatment, it is difficult to reconcile ourselves to such a slovenly mode of interment, although it may be the established system of the country. All the funerals here are in the hands of a company, who, for the privilege of burying the rich at fixed prices, contract to inhume all the poor for nothing. It is hardly to be supposed, that in such a multiplicity of tomb there are not some offensive to good taste. Many are gaudy and fantastical, dressed up with paltry figures of the Virgin and Child, and those tin and tinsel decorations which the rich in faith and poor pocket are apt to set up in Roman Catholic countries – but the generality are of a much nobler order, and I defy any candid traveler to spend a morning in the Cemetery of Pere La Chaise without feeling a higher respect for the French character, and forming a more pleasing estimate of human nature in general.

Thursday, February 05, 2015

Parlez-vous Paris? no. 43 Caroline: Au cimetière du Père-Lachaise

Work on your French while you listen to Caroline talking about Pere-Lachaise.

Wednesday, February 04, 2015

Les Innocents fountain

This fountain is last remnant of the cemetery that was once beneath what would become Les Halles market. The market was torn down in the early 1970s to make way for an incredibly tacky underground shopping mall.

Sunday, February 01, 2015

Wednesday, January 28, 2015

La Morgue de Paris circa 1845

Odd as it may sound, the Paris Morgue, located on the Quai de Marche Neuf, was considered quite a tourist attraction in the 19th century and was often featured in the numerous guides to the city.

Sunday, January 25, 2015

Wednesday, January 21, 2015

Maison Mont Saint-Louis at Pere-Lachaise Cemetery in the 17th century

Located on the spot where Mr. Renault's home was built in the 15th century, the Jesuit retreat eventually fell into ruin after it was abandoned in the late 18th century. It was torn down to make way for Godde's chapelle in 1823.

Labels:

maison,

Mont Louis,

Mont Saint-Louis,

Pere Lachaise,

postcard

Sunday, January 18, 2015

Wednesday, January 14, 2015

Pere-Lachaise in Murray's Handbook to Paris, 1866

Pere la Chaise. On the N.E. of the city. The oldest and largest extramural cemetery in Paris. Now that planted cemeteries are common in England, the visitor will hardly find it worth while to take a drive of near 3 m. to see this cemetery, especially as the height of the trees and the smoke of the Faubourg St. Antoine materially injure the once celebrated view over Paris. Omnibuses run to Pere la Chaise from the Place de la Bastille with correspondence along the Boulevards, and from the Louvre every quarter of an hour. There are guides at the entrance who charge 2 fr. an hour, and it will be the best plan to take one, cautioning him not to employ more than a limited time. A good walker will be able to see all that is interesting in a couple of hours.

The N.E. extremity of the Rue de la Roquette, leading to the cemetery from the Boulevard du Prince Eugene, is filled with makers of sepulchral monuments, dealers in wreaths to decorate the tombs, crosses, etc. The ground now occupied by the cemetery was given to the Jesuits in 1705, and received its name from Pere la Chaise, confessor of Louis XIV, who was then the superior of the order in Paris. On the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1763 it was sold and passed through several hands, until, in 1804, it was purchased by the municipality to be converted into an extra-mural cemetery. Up to this time the dead had been buried in churches or churchyards within the city, and the idea of making a cemetery outside the walls seems to have originated at Francfort, and thence to have been introduced by Napoleon into France, as within the last 25 years into England.

The cemetery has increased in area from about 50 to more than 200 acres. About 50 interments a day take place here; two-thirds of them are in open graves (Fosses Communes), where 40 or 50 coffins are laid side by side and 3 deep in a trench which is then covered over with earth. The charge for this (unless proof of poverty can be adduced) is 20 fr., and it is usual to erect near the spot a small wooden railing and cross, which costs about 15 fr., and a few flowers are usually planted. At the end of 5 years all these railings and crosses are pulled up and the wood given to the hospitals for fuel; the ground is covered with 4 or 5 ft. of earth dug from other graves or from the hill above, and a fresh tier of coffins is deposited.

The next class of graves are the Fosses Temporaires, where for about 50 fr. a separate grave and 10 years' occupation is secured. Here each grave has a little railing, garden, and cross, or chapel. The more solid sepulchral monuments are built on land bought absolutely (concession a perpetuite). The price of a piece' of ground 2 metres (6 ft.) square is 500 fr. There are about 16,000 stone monuments, on which near 5,000,000 pounds have been spent in the last 50 years. The trees have now grown to a great size and make the older part of the cemetery a thick wood. Most of the celebrated Frenchmen of the present century are buried here.

Broad carriage roads lead straight up from the principal entrance; the first turning rt., l'Allee des Acacias, leads to the Jewish cemetery, where Rachel's tomb is the most remarkable object. A little further on we reach the tomb of Abelard and Heloise, which has always attracted much interest. Abelard died in 1142, and was buried 1101 the priory of St. Marcel under the present tomb. Soon afterwards Heloise had his remains removed to the abbey of the Paraclet, of which she was abbess; and on her death, in 1163, she was laid near him. In 1497 their remains were removed into the church of the abbey. In 1792, when the monasteries were dissolved, they were carried in procession by the inhabitants of Nogent-sur-Seine to their parish church. In 1800 their tomb and statues were transferred to the Musee des Monumens Francais, and placed under the canopy of the original tomb of Abelard. In 1817 they were removed to their present place, and the Gothic canopy under which they lie was raised out of the mins of the Abbey of the Paraclet.

Returning to a broad avenue which sweeps round to the l[eft], we come to an open circular space, in the centre of which stands the handsome monument of Casimir Perier (died 1832). The ground rises abruptly behind here, and on the brow some of the handsomest monuments have been placed. The large marble Doric monument to Countess Demidoff, perhaps the most magnificent of all, is immediately above. From the hill higher up the view has been much impeded by the growth of the trees. A path to the right leads to the tombs of B. Constant and Gen. Foy, Manuel the orator, and Beranger the poet (d. 1837). E. of this are monuments to many of Napoleon's marshals-Lefebvre, Massena, Davoust, Mortier, and Suchet. Near the last is tho tomb of Madame Cottin. The grave of Ney (d. 1815) is at an angle between two roads, but without any monument or inscription, in the midst of a pretty flower-garden surrounded by a high enclosure of ivy.

Keeping now towards the N.W., we come to the spot where several of our countrymen are laid, always a melancholy sight in a foreign land. Volney, and Sir Sidney Smith, the defender of Acre, are buried here. Near this is the tomb of Moliere, which was transported from the Musee des Petits Augustins, and adjoining it that of La Fontaine, adorned with subjects taken from his fables. Along the broad road (l'Allee des Marronniers), between these tombs and the English part of the cemetery, are some very fine monuments: those of M. Aguado, a rich banker, of Godoy Prince of Peace, and the Duchess of Duras, are the most remarkable. The lofty pyramid is to the memory of a M. Felix de Beaujour, a rich native of Provence.

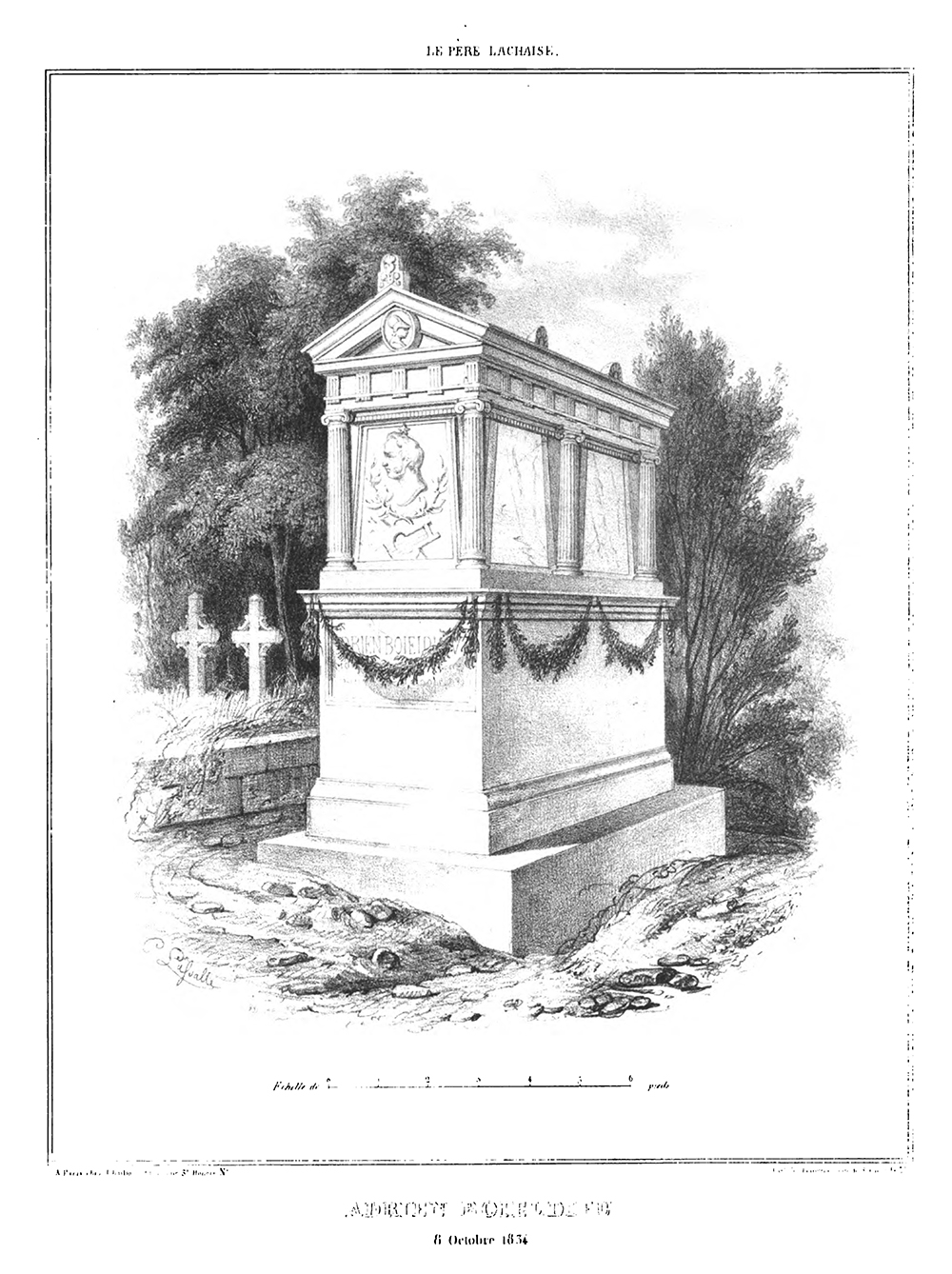

Descending from the N. corner of the grounds towards the chapel are the tombs of Casimir Delavigne the poet, of Balzac the novelist, and of David d'Angers the sculptor. In the N.W. angle is the principal burying-ground at this moment (1864) for the lower orders, and beyond, the Mussulman cemetery, enclosed by walls, in which is the tomb of the Queen and Prince of Oude, on each side and behind which is a large space recently added to the grounds, the present place of interment of the lower orders. The chapel of the cemetery of Pere la Chaise is a plain Doric building, from the steps leading to which is a fine view, in which the towers of Vincennes form an imposing object. There are several English monuments to the W. of the wide avenue which leads past the chapel; and in the angle between the avenues on the S. of it are those of many French actors and artists - Talma, Herold, Bellini, Lebrun, Gretry, Boieldieu, etc. Descending from the chapel to the entrance gate, by a broad alley, are the tombs of Arago, the 2 Viscontis, Delambre the celebrated astronomer, and a short way farther S.E. that of Cuvier. The places of the tombs of the most celebrated personages, not mentioned above, will be found on the accompanying plan.

It is the custom in France for the relations and friends to visit the tombs continually, praying by them, and hanging up garlands of immortelles. On All Souls' Day, 2 Nov., the cemetery is crowded.

When the allies advanced on Paris in 1814, the heights of Pere la Chaise were defended for some time against the Russians, who at the third attempt drove back the defenders and finally bivouacked in the cemetery.

[From A Handbook for Visitors to Paris by John Murray, London, 1866, pp. 211-214]

The N.E. extremity of the Rue de la Roquette, leading to the cemetery from the Boulevard du Prince Eugene, is filled with makers of sepulchral monuments, dealers in wreaths to decorate the tombs, crosses, etc. The ground now occupied by the cemetery was given to the Jesuits in 1705, and received its name from Pere la Chaise, confessor of Louis XIV, who was then the superior of the order in Paris. On the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1763 it was sold and passed through several hands, until, in 1804, it was purchased by the municipality to be converted into an extra-mural cemetery. Up to this time the dead had been buried in churches or churchyards within the city, and the idea of making a cemetery outside the walls seems to have originated at Francfort, and thence to have been introduced by Napoleon into France, as within the last 25 years into England.

The cemetery has increased in area from about 50 to more than 200 acres. About 50 interments a day take place here; two-thirds of them are in open graves (Fosses Communes), where 40 or 50 coffins are laid side by side and 3 deep in a trench which is then covered over with earth. The charge for this (unless proof of poverty can be adduced) is 20 fr., and it is usual to erect near the spot a small wooden railing and cross, which costs about 15 fr., and a few flowers are usually planted. At the end of 5 years all these railings and crosses are pulled up and the wood given to the hospitals for fuel; the ground is covered with 4 or 5 ft. of earth dug from other graves or from the hill above, and a fresh tier of coffins is deposited.

The next class of graves are the Fosses Temporaires, where for about 50 fr. a separate grave and 10 years' occupation is secured. Here each grave has a little railing, garden, and cross, or chapel. The more solid sepulchral monuments are built on land bought absolutely (concession a perpetuite). The price of a piece' of ground 2 metres (6 ft.) square is 500 fr. There are about 16,000 stone monuments, on which near 5,000,000 pounds have been spent in the last 50 years. The trees have now grown to a great size and make the older part of the cemetery a thick wood. Most of the celebrated Frenchmen of the present century are buried here.

Broad carriage roads lead straight up from the principal entrance; the first turning rt., l'Allee des Acacias, leads to the Jewish cemetery, where Rachel's tomb is the most remarkable object. A little further on we reach the tomb of Abelard and Heloise, which has always attracted much interest. Abelard died in 1142, and was buried 1101 the priory of St. Marcel under the present tomb. Soon afterwards Heloise had his remains removed to the abbey of the Paraclet, of which she was abbess; and on her death, in 1163, she was laid near him. In 1497 their remains were removed into the church of the abbey. In 1792, when the monasteries were dissolved, they were carried in procession by the inhabitants of Nogent-sur-Seine to their parish church. In 1800 their tomb and statues were transferred to the Musee des Monumens Francais, and placed under the canopy of the original tomb of Abelard. In 1817 they were removed to their present place, and the Gothic canopy under which they lie was raised out of the mins of the Abbey of the Paraclet.

Returning to a broad avenue which sweeps round to the l[eft], we come to an open circular space, in the centre of which stands the handsome monument of Casimir Perier (died 1832). The ground rises abruptly behind here, and on the brow some of the handsomest monuments have been placed. The large marble Doric monument to Countess Demidoff, perhaps the most magnificent of all, is immediately above. From the hill higher up the view has been much impeded by the growth of the trees. A path to the right leads to the tombs of B. Constant and Gen. Foy, Manuel the orator, and Beranger the poet (d. 1837). E. of this are monuments to many of Napoleon's marshals-Lefebvre, Massena, Davoust, Mortier, and Suchet. Near the last is tho tomb of Madame Cottin. The grave of Ney (d. 1815) is at an angle between two roads, but without any monument or inscription, in the midst of a pretty flower-garden surrounded by a high enclosure of ivy.

Keeping now towards the N.W., we come to the spot where several of our countrymen are laid, always a melancholy sight in a foreign land. Volney, and Sir Sidney Smith, the defender of Acre, are buried here. Near this is the tomb of Moliere, which was transported from the Musee des Petits Augustins, and adjoining it that of La Fontaine, adorned with subjects taken from his fables. Along the broad road (l'Allee des Marronniers), between these tombs and the English part of the cemetery, are some very fine monuments: those of M. Aguado, a rich banker, of Godoy Prince of Peace, and the Duchess of Duras, are the most remarkable. The lofty pyramid is to the memory of a M. Felix de Beaujour, a rich native of Provence.

Descending from the N. corner of the grounds towards the chapel are the tombs of Casimir Delavigne the poet, of Balzac the novelist, and of David d'Angers the sculptor. In the N.W. angle is the principal burying-ground at this moment (1864) for the lower orders, and beyond, the Mussulman cemetery, enclosed by walls, in which is the tomb of the Queen and Prince of Oude, on each side and behind which is a large space recently added to the grounds, the present place of interment of the lower orders. The chapel of the cemetery of Pere la Chaise is a plain Doric building, from the steps leading to which is a fine view, in which the towers of Vincennes form an imposing object. There are several English monuments to the W. of the wide avenue which leads past the chapel; and in the angle between the avenues on the S. of it are those of many French actors and artists - Talma, Herold, Bellini, Lebrun, Gretry, Boieldieu, etc. Descending from the chapel to the entrance gate, by a broad alley, are the tombs of Arago, the 2 Viscontis, Delambre the celebrated astronomer, and a short way farther S.E. that of Cuvier. The places of the tombs of the most celebrated personages, not mentioned above, will be found on the accompanying plan.

It is the custom in France for the relations and friends to visit the tombs continually, praying by them, and hanging up garlands of immortelles. On All Souls' Day, 2 Nov., the cemetery is crowded.

When the allies advanced on Paris in 1814, the heights of Pere la Chaise were defended for some time against the Russians, who at the third attempt drove back the defenders and finally bivouacked in the cemetery.

[From A Handbook for Visitors to Paris by John Murray, London, 1866, pp. 211-214]

Sunday, January 11, 2015

Wednesday, January 07, 2015

"Pere La Chaise and Story of Lavalette" by Grace Greenwood 1867

It was on a Sunday, -- a soft, golden October day, that we drove out to Pere la Chaise, the most beautiful cemetery of Paris. This burial-place is very picturesquely situated on the slope of a hill, northeast of the city, and contains within its walls one hundred and fifty acres. It was consecrated in 1804, and named after Pere la Chaise, who was the superior of a religious establishment which once stood on the ground.

This cemetery is like a vast royal garden, full of all beautiful and rare trees and plants, overflowing with flowers, crowded with little chapels, monuments and tombs. Of the last there are sixteen thousand; and the cost of the monuments is estimated at one hundred and twenty millions of francs.

I cannot tell you how lovely and solemn this "city of the dead" seemed to me on that calm Sunday. A sweet south wind was blowing, which gently shook down from trees and vines showers of autumn leaves, that rustled and fluttered about the monuments, eddied in the grass, and rolled along the paths in little drifts of crimson and gold. The soft, mild sunshine seemed to fall tenderly from heaven, like a sign of God's acceptance and forgiveness of that multitude of his erring children, prostrate and silent in the last sleep. The ivy and some other vines were yet green, and clung about tombs like kindly recollections, -- flowers of many kinds, -- roses that reminded one of "the Rose of Sharon"; the azure heliotrope, the brave, constant little mignonette, and the tender myrtle, made sweetness and brightness in the shadow of cypresses and massive tombs; while on many a humble, unmarked mound, and little baby grave, half hidden in the grass, grew fragrant blue violets, glistening with dew, and looking like watchful, loving eyes, brimmed with tears.

So graced and watched over, no grave could look lonely and neglected; but there are other marks of faithful and affectionate remembrance here. Lying on the mounds, and hanging on crosses and monuments, are innumerable wreaths, made of a fadeless flower called the Immortelle; and over many graves the tombs are built in the form of little chapels, or oratories, where mourners go for prayer and meditation; where alone, secluded from all the world, they can spend hours in devotion, in thinking beautiful thoughts, and recalling sweet, sad memories of their dear lost ones, in weeping out their griefs and regrets, and in cherishing precious hopes of an eternal reunion in the blessedness and rest of heaven. In most of these oratories fresh wreaths or bouquets are left daily; and in some, wax tapers are kept burring before the image of our Lord Jesus, or Mary his mother.

The French are usually considered light, irreligious, and heartless; but visiting this cemetery, and seeing what loving care they have for their dead, is enough to convince any one that very many of them must be true-hearted, serious minded, full of good and tender feeling.

It is so much better to have our burial-places pleasant, shady spots, where flowers will bloom luxuriantly, and birds will sing, -- where little children, and, we may hope, angels, will love to come, than to have them shut up in by city walls, crowded and damp and dark, or away off on some bleak hillside, exposed to wind and sun, overgrown with rank weeds, neglected and forgotten.

The first monument that attracted our attention was one in the form of a small Gothic chapel. This was erected to the memory of Abelard and Heloise, two famous, unfortunate lovers of the twelfth century. Their lives were very sorrowful, for they were parts, -- Abelard became a priest and Heloise an abbess, -- but they always loved one another, and were buried side by side. Their bodies were removed several times, and now their dust lies here. Reclining under a canopy on the monument are two marble statues of the lovers, dressed in the costume of their time, lying apparently asleep, and looking very peaceful, though somewhat weary and sad.

This is the most interesting tomb in all the cemetery to romantic people, but I think you would feel as much emotion at the grave of the brave Marshal Ney, who was shot for his devotion to Napoleon, -- at the tomb of the wise and good La Fontaine,-- or that of Bernardin St. Pierre, the author of the exquisite story of "Paul and Virginia," -- or of Madame Cottin, who wrote "Elizabeth, or the Exiles of Siberia," -- or of the the Count Lavalette (pictured right, today).

The most magnificent monument at Pere la Chaise is that of a Countess Demidoff. It consists of ten marble columns, resting on a wide, massive base, and supporting an entablature, under which is a sarcophagus, on which is a sculptured cushion, bearing the arms and the coronet of the Countess. This great, costly monument, which stands on a hill, overlooking the whole cemetery, is erected to one who was merely rich and titled. It seemed to me, in its massiveness and white beautify, but a pile of arrogance and pride, haughtily towering above the graves of heroes and poets, the great and good, and defying death itself. I thought I should rather lie in the lowliest grave of the poor, and have the violets creep over me, than lie in state in that pompous mausoleum, -- that dead woman's palace.

I have spoken above of the tomb of Count Lavalette. Possibly some of you may be unacquainted with his story; I will relate it at a venture: --

LAVALETTE AN HIS WIFE

Marie Chamans, Count de Lavalette, was born at Paris in 1769. He was the son of a shopkeeper, but he received a liberal education, and studied law. When the great Revolution broke out he joined the National Guard; yet at the storming of the Tuileries he nobly risked his life in defending Louis XVI and his family from the fury of the mob. He was filled with horror and disgust at the atrocities of the revolutionists, left France and joined the army abroad. After the battle of Arcola, Napoleon, then General Bonaparte, made him his aid-de-camp, and from that time manifested towards him the utmost affection and confidence. In this instance he showed great good sense and taste, selecting an officer and a friend, for Lavalette was a man of superior talents, remarkable sagacity, a generous spirit, and rare elegance of manner. He accompanied Napoleon on his expedition to Egypt; but a few weeks previous, married Mademoiselle Emilie de Beauharnais, a niece of Josephine, Madame Bonaparte. This marriage was planned, almost commanded by Napoleon, but it proved a very happy one. The bride was young, beautiful, good, and very noble; while Lavalette was amiable, affectionate and faithful, -- loving and admiring his Emilie with all his heart.

Lavalette encountered many dangers in Egypt, in battle and from the plague, but he finally returned to his country and home in safety.

When Napoleon became emperor, he made Lavalette a Count of the empire, and his wife mistress of the robes to the Empress; but when her aunt was divorced, Emilie left the court, and retired to private life.

On the abdication and first exile of Napoleon, Lavalette submitted, and promised allegiance to Louis XVIII. He would have remained faithful, had not this king proved himself a stupid tyrant, and a coward, unfit to reign. When Napoleon returned from Elba, and Louis fled from France, Lavalette gladly went back to the service of his beloved Emperor.

When, after the battle of Waterloo, Napoleon left France for his long, last exile, there was a sad and tender parting between him and his faithful friend. After the restoration fog Louis XVIII, Lavalette was advised to fly from his country; but his wife was ill at the time, and he could not believe Louis base and cruel enough to punish him for his attachment to his old master. However, he was arrested and imprisoned in the Conciergerie, the gloomy, terrible prison in which Marie Antoinette, Madame Roland, and may other noble victims of the Revolution, were confined. Here, in a wretched apartment, -- dark, cold, and damp, -- he sighed away his weary days from July to November, when he was brought to trial, and condemned to die by the guillotine, on the 21st of December.

As soon as she heard of this sentence, Madame Lavalette went to the King, flung herself at his feet, and implored him to spare the life of her husband. So beautiful was her face, even though bathed in tears, -- so noble and graceful her manner, -- such sweetness was in her voice, such pathos in her words, that only very hard-hearted, revengeful man could have resisted her. This miserable king, however, refused to grant her prayer, though he cruelly encouraged her at first. She went a second time, but was repulsed from his presence, and actually sat for more than an hour alone, not he stone steps of the palace, in utter grief and despair.

But as she sat there, weeping, shunned and abandoned by all the world, suddenly a strong, comforting angel seemed to whisper to her soul a brave plan for saving her beloved husband, and she rose up with a noble purpose in her heart, and a prayer on her lips for heavenly help and strength.

She was in the habit o dining with Lavalette daily, sometimes accompanied by her daughter, a lovely young girl, and sometimes by a faithful old nurse. One the last day but one preceding that fixed on for the Count's execution, Emilie said to him, "There no longer remains for us any hope but in one plan; you must leave here at eight o'clock, in my clothes, and go in my sedan chair to where Monsieur Baudus will have a cabriolet waiting to conduct you to a place of safety, where you will remain till you can quit the country."

Lavalette was astounded: he thought the plan of his wife a made and hopeless one, and so he told her. But she was calm and firm, and replied: "No objections; your death will be mine; so do not reject my proposal. My conviction of its success is deep, for I feel that God sustains me."

It was in vain that Lavalette represented how almost impossible it would be for him to so disguise himself as to deceive the sharp eyes of the turnkeys and soldiers, whom she was obliged to pass every night on leaving the prison; and the probability that, should he escape, they would ill-treat, perhaps kill her, in their rage. She turned very pale, but she was firm, and at last wrung from him a promise to attempt to execute her plan on the following day, his last day of life, if it should fail.

When Madame Lavalette came for her last visit, she was accompanied by her daughter Josephine and the old nurse. She wore over her dress a merino pelisse, lined with fur, and brought her a black silk petticoat. She said to her husband, "These will disguise you perfectly. Before going into the outer room, be sure to draw on your gloves, and put my handkerchief to your face. Walk very slowly, leaning on Josephine, and take care to stoop as you pass through these low doors, for if they should catch the feathers of your bonnet all would be lost. The jailers will be in the anteroom, and remember the turnkey always hands me out. The chair will be near the staircase. Monsieur Baudus will meet you soon and point our your hiding-place. Mind my directions, -- keep calm. God guide and protect you, my dearest husband."

She also gave some directions to her daughter, which the child promised to follow carefully. After dinner the prisoner retired behind a large screen, where his wife dressed him in the petticoat and pelisse she had brought, and put her bonnet on his head, all the while repeating, "Mind you stoop at the doors, -- be sure you walk through the hall slowly, like a person worn with suffering. What do you think of your papa," she said to Josephine, "will he do?"