ONE of our pleasantest visits was to Pere 1a Chaise, the national burying-ground of France, the honored resting place of some of her greatest and best children, the last home of scores of illustrious men and women who were born to no titles, but achieved fame by their own energy and their own genius. It is a solemn city of winding streets, and of miniature marble temples and mansions of the dead gleaming white from out a wilderness of foliage and fresh flowers. Not every city is so well peopled as this, or has so ample an area within its walls. Few palaces exist in any city, that are so exquisite in design, so rich in art, so costly in material, so graceful, so beautiful.

We had stood in the ancient church of St. Denis, where the marble effigies of thirty generations of kings and queens

Jay stretched at length upon the tombs, and the sensations invoked were startling and novel; the curious armor, the obsolete costumes, the placid faces, the hands placed palm to palm in eloquent supplication-it was a vision of gray antiquity. It seemed curious enough to be standing face to face, as it were, with old Dagobert I, and Clovis and Charlemagne, those vague, colossal heroes, those shadows, those myths of a thousand years ago! I touched their dust-covered faces with my finger, but Dagobert was deader than the sixteen centuries that have passed over him, Clovis slept well after his labor for Christ, and old Charlemagne went on dreaming of his paladins, of bloody Roncesvalles, and gave no heed to me.

The great names of Pere la Chaise impress one, too, but differently. There the suggestion brought constantly to his

mind is, that this p1ace is sacred to a nobler royalty-the royalty of heart and brain. Every faculty of mind, every noble trait of human nature, every high occupation which men engage in seems represented by a famous name. The effect is a curious medley. Davoust and Massena, who wrought in many a battle-tragedy, are here, and so also is Rachel, of equal renown in mimic tragedy on the stage. The Abbe Sicard sleeps here -- the first great teacher of the deaf and dumb-a man whose heart went out to every unfortunate, and whose life was given to kindly ofttimes in their service; and not far on, in repose and peace at last, lies Marshal Ney, whose stormy spirit knew no music like the bugle call to arms. The man who originated public gas-lighting, and that other benefactor who introduced the cultivation of the potato and thus blessed millions of his starving countrymen, lie with the Prince of Masserano, and with exiled queens and princes of Further India. Gay-Lussac the chemist, Laplace the astronomer, Larrey the surgeon, de Seze the advocate, are here, and with them are Talma, Bellini, Cherubini, de Balzac, Beaumarchais,

Beranger, Moliere and Lafontaine, and scores of other men whole names and whose worthy labors are as familiar in

the remote by-places of civilization as are the historic deeds of the kings and princes that sleep in the marble vaults of St. Denis.

But among the thousands and thousands of tombs in Pere la Chaise, there is one that no man, no woman, no youth of

either seX, ever passes by without stopping to examine. Every visitor has a sort of indistinct idea of the history of its dead, and comprehends that homage is due there, but not one in twenty thousand clearly remembers the story of that tomb and its romantic occupants. This is the grave of Abelard and Heloise--a grave which has been more revered, more widely known, more written and sung about and wept over, for seven hundred years, than any other in Christendom, save only that of the Saviour. All visitors linger pensively about it; all young people capture and carry away keepsakes and mementoes of it; all Parisian youths and maidens who are disappointed in love come there to bail out when they are full of tears; yea, many stricken lovers make pilgrimages to this shrine from distant provinces to weep and wail and "grit" their teeth over their heavy sorrows, and to purchase the sympathies of the chastened spirits of that tomb with with offerings of immortelles and budding flowers.

Go when you will, you find somebody snuffling over that tomb. Go when you will, you find it furnished with those bouquets and immortelles. Go when you will, you find a gravel-train from Marseille arriving to supply the deficiencies caused by memento-cabbaging vandals whose affections have miscarried.

[From chapter XV Innocents Abroad, 1869]

Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Sunday, December 28, 2014

Sunday, December 21, 2014

Sunday, December 14, 2014

Tuesday, December 09, 2014

Identifying Everyone Buried in Père-Lachaise, or M. Rogers and Son Try to do the Impossible in 1816

[This is a revised version of an article I wrote for the Association of Gravestone Studies Quarterly]

On May 21, 1804, when Le Cimetière Mont-Louis (officially known as Le Cimetiere de l'Est but eventually more popularly as Père-Lachaise) opened on the site of a former Jesuit retreat set amidst 42 acres of sweeping garden lanes that were both part of the original estate and sculpted according to a plan laid down by renowned architect Alexandre-Theodore Brongniart (buried in division 11), it was unlike any burial site that anyone in Paris could remember.

Besides the temporary grave markers for the common man, woman and child set on a westward-facing slope amidst cypresses, willows, and shrubs and flowers of all shapes, colors and sizes, if one had enough money they could actually purchase a permanent burial site, a concession perpetuite.

This new burial scheme was remarkable for its novelty. Parisian burial grounds were usually laid out in small parish cemeteries, on flat ground, making for easy interment and, presumably maintenance. Nor were most graves permanent and rarely, if ever, memorialized. After a predetermined time allowed for decomposition, most bodies were removed and the bones placed in a nearby charnel house. But the city’s ancient central cemetery, Les Innocents, which had been recycling human remains for centuries eventually became too much for the community to bear – literally bodies were falling into basements and the stench became unbearable for nearby residents.

Although the process of closing the city’s unhygienic and overcrowded church cemeteries had begun during the reign of Louis XVI and accelerated in the early years of the Revolution, church cemeteries, particularly anathema to the new revolutionary ideals after 1789, could no longer be tolerated.

Of the "new" Paris cemeteries available to city residents in the first years of the 19th century, Montmartre was on the site of two older burial grounds in a former quarry, while Vaugirard and Sainte Catherine-Clamart were laid out on flat ground in previously-used burial spaces, both easily accessible for the residents in the southwestern and southern portions of the city respectively.

With the exception of Père-Lachaise, none of these cemeteries were by any means “new.” Although formally established in 1825, Montmartre, also known as Le Cimetière du Nord, the Northern Cemetery, was in fact on the site of two older burial grounds in a gypsum quarry and throughout the first twenty or so years of the 19th century all authors refer to it’s existence. Earlier iterations of Vaugirard dated to the late 18th century (and is not the same as the present Vaugirard Cemetery).

Clamart and Sainte-Catherine were next-door neighbors near present-day Boulevard Saint-Marcel, so to speak, burial grounds that also pre-dated the opening of new cemeteries. Clamart was located just about where Square Scipion is located today, at the corner of what is now rue du Fer a Moulin and rue Scipion; Sainte-Catherine was located under what is now Boulevard Saint-Marcel, roughly between rue Fosses de Saint-Marcel and rue Scipion.

But Père-Lachaise would be different.

It was the farthest from the city proper, it lay uphill, and was certainly not readily or easily accessible to city residents. (By contrast, the parish cemetery in the nearby small village of Charonne, which exists today, was still in operation serving the local residents.) The fact that the government even considered such a unique site as the old Jesuit retreat, with its overgrown, sloping paths and vistas of the city to the west and Vincennes to the east showed a refreshing imagination in designing a place for the city’s future dead. Yet what seemed so different about Père-Lachaise apparently made it more, not less attractive.

The man responsible for all this was Nicholas Frochot (division 37), then Prefect of the Seine, an administrative post that was part city mayor of Paris and governor of much of what is now the Isle de France. Frochot arranged for the purchase of the former Jesuit property then owned by Louis Baron-Desfontaines (division 22), quite probably at the suggestion of the man who appointed him, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Whether it was Frochot or Napoleon who had the original idea to locate the city’s newest cemetery on the old Jesuit home, the Prefect set to work to make this one of the most unique burial grounds in the world. Relying on Brongniart's architectural expertise and building on the existing gardens, orchards, and walking paths of the old Jesuit retreat, graves large and small were laid out more or less at random, scattered beneath cypresses and willows.

Aside from establishing a totally new burial space of flowing gardens, winding paths and rambling trees, arbors and shrubs, Frochot also established the concession perpetuite, or permanent burial site. For a fee, a family could purchase space that was to be held in perpetuity – as long as they agreed to maintain the grave. Any abandoned or derelict gravesite would revert to the cemetery to be reused. An area was also set aside for "temporary" burials (fosses commune). For a smaller fee than the concession perpetuite, a family could “lease” a plot of ground for a given period after which the remains would be removed, placed in the ossuary and the ground reused.

The truly amazing thing was that for the first time in the city's history, men, women, children, families large and small, nearly all classes of people now had a space for memorialization. And those memorials could, with a little extra money, be rendered permanent. Novel indeed!

Parisians were on the cusp of a fundamental reevaluation about death and the dead, about how they wanted to remember and be remembered après la mort. Indeed, there soon developed a broadly keen interest in finding and memorializing burial sites. Equally remarkable was how quickly these new ideas about burial and memorialization resulted in the demand for printed guides to the monuments of the famous and near-famous.

1809, Antoine Caillot creates the first guide to Paris Cemeteries

In 1809 Antoine Caillot produced what is probably the first guidebook to the cemeteries of Paris. His Voyage Religieux et Sentimental aux Quatre Cimetières de Paris focused on four of the prominent cemeteries then in use just outside the city proper: Montmartre, Mont-Louis (Père-Lachaise), Vaugirard and Clamart-Sainte Catherine. Aside from providing background information for each burial ground and discussing the religious significance of many of the burials, Caillot’s emphasis was to identify and describe notable interments and their markers. In regards to Père-Lachaise he listed 38 burials along with details and epitaphs.

When Caillot published his guide to Paris cemeteries in 1809 there were probably less than 200 burials in Pere-Lachaise, the largest of the "new" city cemeteries. Indeed, it has often been argued that the popularity of the cemetery would not actually take off until 1817 when the remains -- or what passed for remains -- of writers La Fontaine and Moliere and the star-crossed 12th century lovers the abbess Heloise Argenteuil and noted scholar and theologian Pierre Abelard, along with pieces of Heloise’s Paraclet Abbey used to build the two lovers' tomb, were removed to "Mont-Louis," to Pere-Lachaise.

It is my belief there was already a growing interest in memorialization in Paris underway well before 1817.

After his death in 1813 the imposing memorial of acclaimed French poet Jacques Delille became a place of pilgrimage for many Parisians. In fact, Delille’s tomb was located at the end of a small glen (bosquet) that itself would quickly fill up with numerous other luminaries: architect Alexandre Theodore Brongniart (1813), statesman Pierre Louis Ginguene (1816), and the opera singer Andre Ernest Gretry (1813).

The writer Stansilas Boufflers (1815) was even buried in the same enclosure with Delille and the body of Saint-Lambert was removed from Vaugirard and reinterred next to Delille as well. Delille’s “bosquet” remains largely intact today.

These first years saw numerous other notables interred on "Mont-Louis," individuals who in their own day attracted wide notoriety and attention: Antoine Parmentier (1813), who brought the potato to prominence in France, Marshal Michel Ney and comte Charles de La Bedoyere, both executed in 1815 for their support of Napoleon’s return (paying the ultimate price for his eventual failure).

1815-1816, C. P. Arnaud and Pietresson de Saint-Aubin

The interest in memorialization of the common man as well as the growing curiosity to see the burial sites of the notables of Parisian society soon produced the first two really serious attempts to graphically locate the graves of the latter.

In October of 1815, C. P. Arnaud produced a map of Père-Lachaise, which would eventually accompany his Recueil de Tombeaux des Quatre Cimetières de Paris (1817). While similar to Brongniart’s 1813 map, Arnaud’s included existing structures such as the abandoned mansion and the concierge’s house. He then proceeded to identify the locations of 89 monuments in (some including multiple burials), noting them on his map as he walked the cemetery.

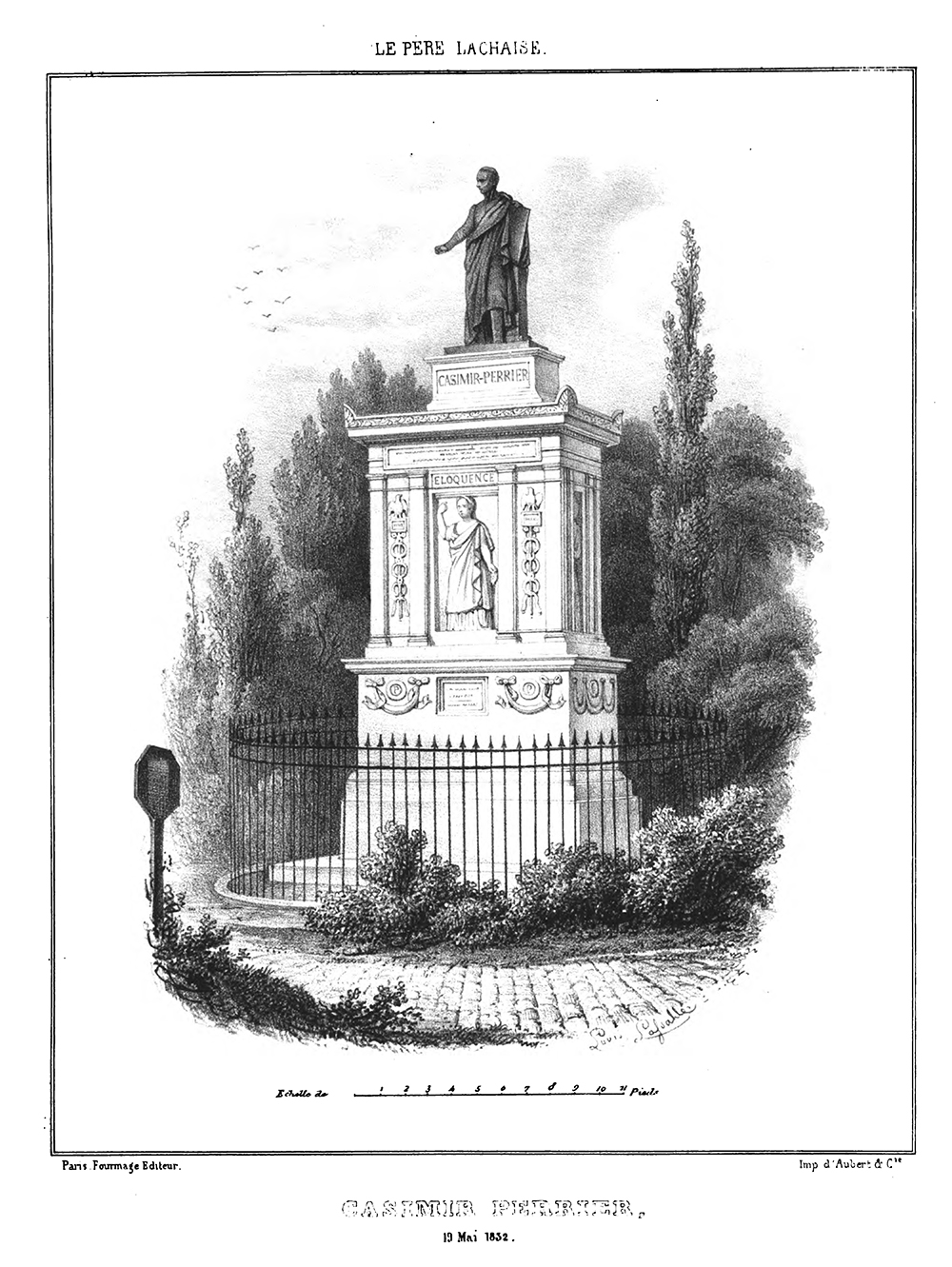

Arnaud then discussed 21 monuments in the text, even providing 10 of his entries with prints. (The idea of producing prints of the monuments of the famous and near-famous would indeed become quite popular over the succeeding decades. In fact, in 1823 Arnaud would produce a small volume of drawings of the doors of 18 mausoleums, with prints of each one, and in 1825 a second volume of his cemetery transcriptions. The latter would cover 33 monuments (5 repeated from his 1817 study), also with prints of 30 monuments.

In his 1816 guide to “day trips” from Paris, Dictionnaire Historique Topographique et Militaire de Tous les Environs de Paris, Pietresson de Saint-Aubin may have been the first writer of a general tour of Paris to focus on the four cemeteries of Vaugirard, Montmartre, Sainte-Catherine and of course, Père-Lachaise, as destinations worth exploring. (He included 37 entries for Père-Lachaise, “Mont-Louis.”) Building on his 1816 study, a decade later Saint-Aubin, too, would produce his own guide to Paris cemeteries: Promenade aux Cimetieres de Paris, aux Sepultures Royales de Saint-Denis et aux Catacombes.

These early efforts by Caillot and Saint-Aubin to identify the more well-known tombs at Père-Lachaise, hinted at the stories that lay beneath and around those handful of burials. Arnaud took their work to the next level and sought to locate those more well-known burials on a map as well as provide prints of some of them (making it easier to find them perhaps), all of which helped advance this new attention to who was buried where in Paris. And of course it also helped raised the exposure of Père-Lachaise as a place to consider spending eternity.

This interest in who was buried in Père-Lachaise, this new phenomenon of looking at death in a wholly different way through memorialization and pilgrimage, quickly culminated in a truly remarkable study of burials in the city's largest and most well-known cemetery.

1815-1816, Roger & Son raise the bar

A year before the transfer of the remains of Moliere, La Fontaine and Heloise and Abelard to Père-Lachaise in 1817, a father and son team published what must rank as one of the most unique study of any western cemetery. Published in Paris in 1816, Le Champ du Repos, ou Le Cimetiere de Mont-Louis, dit du Pere Lachaise by Roger et Fil is an exhaustive two-volume series listing every one of the more than 2,100 burials in the cemetery comprising what was then known about everyone buried in Père-Lachaise.

This work must certainly rank as the seminal study of the earliest burials in the cemetery: What the authors attempted to do, and very nearly succeeded, was to identify every known grave at the time, including even the temporary ones.

How did they do it?

First, they provided a handy map of the cemetery using major landmarks as a means of breaking the cemetery into manageable areas.

The various sections of the two volumes are broken down by series, which correspond to particular areas on the map, using letters A-F as identifiers that correspond to an outstanding landmark in that section:

The two volumes record 2,174 burials in 2,091 entries; of that number 168 list no death year and 33 list a year but no date. Two hundred sixty-six locations are presently known. Almost all are individual entries (although there are occasions when multiple individuals are buried in the same location).

The Rogers began by listing every grave with all the details inscribed on each stone or marker, including epitaphs and then assigning a number to each grave. They then sketched out each grave memorial or marker, and fairly accurate illustrations they are, right down to writing the deceased's name on every drawing (figure 7).

The finished sketched illustration (planche or “plate”) was given a number that corresponded to the grave listing and each drawing was then grouped together into a series of 37 illustration “maps” (figure 8). They even sketched out the markers for the seventeen burials that had no inscription at all and four where they couldn’t read the inscriptions.

Rogers' illustrations demonstrate an amazing attention to detail. For example, several of the graves in figure 9 look pretty much today the way the Rogers sketched them, in particular poet Jacques Delille (the large building in the center) and Alexandre Brongniart, the architect of the cemetery's original layout (located just to the right of Delille); both men buried in present-day division 11.

Did the Rogers sketch the graves and list them in the order they found them? In other words, did they walk and sketch the graves as they walked along? This seems less clear today.

By breaking the cemetery down into clearly defined “sections” they clearly attempted to narrowly locate each grave to be sure. For example, the most temporary of burials, the fosses commune, are nearly all found on plates 34-36 in what is today divisions 57-59. Of the 266 known locations we find some pattern to be sure: in the illustration figure 9, most of those graves are in fairly close proximity to each other (today).

On the other hand, to list two examples, of the 14 known burial locations found in division 4, the listings in Roger are scattered among plates 21, 23, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 and 37, while the 15 known burials in division 8 are found on plates 17, 18, 19 and 21.

It's therefore possible that there was some order in in where Rogers found the grave but it's not clear what that order was, at least not precisely. It's therefore likely that whatever systematic plan they used is not obvious today in how the graves are listed or sketched out.

And, while it’s probably safe to say that many of the graves were near one another in some fashion. beyond that we can’t be sure of exactly how the Rogers’ approached organizing their layouts.

Nor does it appear that they listed the gravesites by date of death. Here again there is occasionally a pattern, but that might be just coincidental to the actual burials themselves. Someone who died on one day, for example, might be buried near someone who died a week earlier simply by virtue of that space being more “available.”

For example, there appears a clear chronological order on plates 1-5: all but 12 of the 63 entries in plate 1 are listed in chronological order and the next four plates also demonstrate a chronology approach to listing them. The remaining plates, however, list burials with random death dates, with the occasional return to a chronological listing (see for example, plates 28-30). Indeed, nearly all the burials noted on plate 19 occurred February through March of 1815, yet the burials on plate 21 occurred between 1810 and 1814.

What complicates matters was the distinctive nature of Père-Lachaise itself (see for example figure 2). We know from early prints and observations by visitors during the early years of the cemetery that burials were scattered here-and-there, markers often set off by themselves, rather like many burial stones in Mt. Auburn Cemetery (Cambridge, MA) today. Thus, it’s probably safe to say that the earliest burials, aside from those “temporary” ones, were randomly located around the “grounds.”

As one English traveler observed in 1822, the cemetery was “a wilderness of little enclosures . . . almost every one profusely planted with flowers, and overshadowed by poplar, cypress, weeping willow, and arbor vitae, interspersed among the flowering shrubs and fruit trees.” That would certainly make laying out any systematic plan challenging.

Finally, the Rogers’ attempt to locate and sketch each and every grave in the cemetery leaves us with the curious puzzle of why they left some burials out of their collection. A quick analysis of our sources shows that they did not record at least 9 listed by Caillot in 1809 and at least 41 listed on Arnaud’s map of 1815 are not found in Roger. For example, one of those notable graves listed on Arnaud’s map but not in Roger was wealthy negociant Pierre Gareau, who died on August 30, 1815. Gareau’s monument was then and still is topped by a life-size statue of a sitting woman with her hands brought up to her face.

It would seem that the Rogers did not refer to any older source when compiling their listings. But we’ll probably never know for certain.

What is certain is that the Rogers comprehensive and exhaustive efforts to find, identify, transcribe and then illustrate each and every monument and marker in the cemetery is nothing short of amazing. Their work should serve as inspiration for all of us who toil in the champs du repos, who seek to capture and preserve the memories of those who came before us, of “those who sleep the sleep that knows no waking.”

Just the beginning

Following the publication of Le champ du repos, the interest in identifying burials in Père-Lachaise intensified throughout the first half of the century. In 1821 F. G. T. de Jolimont published Les Mausolees de Paris, a detailed study of 51 notable burials in the cemetery with 42 accompanying prints. Beginning as early as 1822, Galignani, the Paris-based English-language publisher of guides to the city, began including itineraries to the major cemeteries, a trend they would continue in each annual edition for years to come. Baedeker guides would also pick up the same theme, including the major cemeteries, especially Père-Lachaise in its suggested itineraries.

In the 1820s Marchant de Beaumont published at least three separate guides to Père-Lachaise, and in 1832 Louis M. Normand produced a detailed architectural study of the larger monuments in the city’s cemeteries, including nearly many in Père-Lachaise. What may have been an attempt to emulate the work of the Rogers, in 1855 F. T. Salomon, published Le Père-Lachaise: Recueil General, an incredible effort to list more than 16,000 permanent concessions and then locate them all on the accompanying map.

Père-Lachaise long ago passed from its origins as a garden or pastoral cemetery and is today a true necropolis, a city of the dead with little houses lining paved streets just as you might find in any French village.

Electronic (pdf) downloads of the Roger volumes (free):

Volume 1

Volume 2

For more information about the cemetery today visit: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cimetière_du_Père-Lachaise

On May 21, 1804, when Le Cimetière Mont-Louis (officially known as Le Cimetiere de l'Est but eventually more popularly as Père-Lachaise) opened on the site of a former Jesuit retreat set amidst 42 acres of sweeping garden lanes that were both part of the original estate and sculpted according to a plan laid down by renowned architect Alexandre-Theodore Brongniart (buried in division 11), it was unlike any burial site that anyone in Paris could remember.

|

| Brongniart map, 1813 |

Besides the temporary grave markers for the common man, woman and child set on a westward-facing slope amidst cypresses, willows, and shrubs and flowers of all shapes, colors and sizes, if one had enough money they could actually purchase a permanent burial site, a concession perpetuite.

This new burial scheme was remarkable for its novelty. Parisian burial grounds were usually laid out in small parish cemeteries, on flat ground, making for easy interment and, presumably maintenance. Nor were most graves permanent and rarely, if ever, memorialized. After a predetermined time allowed for decomposition, most bodies were removed and the bones placed in a nearby charnel house. But the city’s ancient central cemetery, Les Innocents, which had been recycling human remains for centuries eventually became too much for the community to bear – literally bodies were falling into basements and the stench became unbearable for nearby residents.

Although the process of closing the city’s unhygienic and overcrowded church cemeteries had begun during the reign of Louis XVI and accelerated in the early years of the Revolution, church cemeteries, particularly anathema to the new revolutionary ideals after 1789, could no longer be tolerated.

Of the "new" Paris cemeteries available to city residents in the first years of the 19th century, Montmartre was on the site of two older burial grounds in a former quarry, while Vaugirard and Sainte Catherine-Clamart were laid out on flat ground in previously-used burial spaces, both easily accessible for the residents in the southwestern and southern portions of the city respectively.

With the exception of Père-Lachaise, none of these cemeteries were by any means “new.” Although formally established in 1825, Montmartre, also known as Le Cimetière du Nord, the Northern Cemetery, was in fact on the site of two older burial grounds in a gypsum quarry and throughout the first twenty or so years of the 19th century all authors refer to it’s existence. Earlier iterations of Vaugirard dated to the late 18th century (and is not the same as the present Vaugirard Cemetery).

Clamart and Sainte-Catherine were next-door neighbors near present-day Boulevard Saint-Marcel, so to speak, burial grounds that also pre-dated the opening of new cemeteries. Clamart was located just about where Square Scipion is located today, at the corner of what is now rue du Fer a Moulin and rue Scipion; Sainte-Catherine was located under what is now Boulevard Saint-Marcel, roughly between rue Fosses de Saint-Marcel and rue Scipion.

But Père-Lachaise would be different.

It was the farthest from the city proper, it lay uphill, and was certainly not readily or easily accessible to city residents. (By contrast, the parish cemetery in the nearby small village of Charonne, which exists today, was still in operation serving the local residents.) The fact that the government even considered such a unique site as the old Jesuit retreat, with its overgrown, sloping paths and vistas of the city to the west and Vincennes to the east showed a refreshing imagination in designing a place for the city’s future dead. Yet what seemed so different about Père-Lachaise apparently made it more, not less attractive.

|

| 1815, attributed to Courvoisier |

Whether it was Frochot or Napoleon who had the original idea to locate the city’s newest cemetery on the old Jesuit home, the Prefect set to work to make this one of the most unique burial grounds in the world. Relying on Brongniart's architectural expertise and building on the existing gardens, orchards, and walking paths of the old Jesuit retreat, graves large and small were laid out more or less at random, scattered beneath cypresses and willows.

Aside from establishing a totally new burial space of flowing gardens, winding paths and rambling trees, arbors and shrubs, Frochot also established the concession perpetuite, or permanent burial site. For a fee, a family could purchase space that was to be held in perpetuity – as long as they agreed to maintain the grave. Any abandoned or derelict gravesite would revert to the cemetery to be reused. An area was also set aside for "temporary" burials (fosses commune). For a smaller fee than the concession perpetuite, a family could “lease” a plot of ground for a given period after which the remains would be removed, placed in the ossuary and the ground reused.

The truly amazing thing was that for the first time in the city's history, men, women, children, families large and small, nearly all classes of people now had a space for memorialization. And those memorials could, with a little extra money, be rendered permanent. Novel indeed!

Parisians were on the cusp of a fundamental reevaluation about death and the dead, about how they wanted to remember and be remembered après la mort. Indeed, there soon developed a broadly keen interest in finding and memorializing burial sites. Equally remarkable was how quickly these new ideas about burial and memorialization resulted in the demand for printed guides to the monuments of the famous and near-famous.

1809, Antoine Caillot creates the first guide to Paris Cemeteries

In 1809 Antoine Caillot produced what is probably the first guidebook to the cemeteries of Paris. His Voyage Religieux et Sentimental aux Quatre Cimetières de Paris focused on four of the prominent cemeteries then in use just outside the city proper: Montmartre, Mont-Louis (Père-Lachaise), Vaugirard and Clamart-Sainte Catherine. Aside from providing background information for each burial ground and discussing the religious significance of many of the burials, Caillot’s emphasis was to identify and describe notable interments and their markers. In regards to Père-Lachaise he listed 38 burials along with details and epitaphs.

When Caillot published his guide to Paris cemeteries in 1809 there were probably less than 200 burials in Pere-Lachaise, the largest of the "new" city cemeteries. Indeed, it has often been argued that the popularity of the cemetery would not actually take off until 1817 when the remains -- or what passed for remains -- of writers La Fontaine and Moliere and the star-crossed 12th century lovers the abbess Heloise Argenteuil and noted scholar and theologian Pierre Abelard, along with pieces of Heloise’s Paraclet Abbey used to build the two lovers' tomb, were removed to "Mont-Louis," to Pere-Lachaise.

|

| tomb of Heloise and Abelard with the old Jesuit mansion on the hilltop in the background |

It is my belief there was already a growing interest in memorialization in Paris underway well before 1817.

After his death in 1813 the imposing memorial of acclaimed French poet Jacques Delille became a place of pilgrimage for many Parisians. In fact, Delille’s tomb was located at the end of a small glen (bosquet) that itself would quickly fill up with numerous other luminaries: architect Alexandre Theodore Brongniart (1813), statesman Pierre Louis Ginguene (1816), and the opera singer Andre Ernest Gretry (1813).

The writer Stansilas Boufflers (1815) was even buried in the same enclosure with Delille and the body of Saint-Lambert was removed from Vaugirard and reinterred next to Delille as well. Delille’s “bosquet” remains largely intact today.

|

| tomb of Jacques Delille, division 11, 1821 |

1815-1816, C. P. Arnaud and Pietresson de Saint-Aubin

The interest in memorialization of the common man as well as the growing curiosity to see the burial sites of the notables of Parisian society soon produced the first two really serious attempts to graphically locate the graves of the latter.

In October of 1815, C. P. Arnaud produced a map of Père-Lachaise, which would eventually accompany his Recueil de Tombeaux des Quatre Cimetières de Paris (1817). While similar to Brongniart’s 1813 map, Arnaud’s included existing structures such as the abandoned mansion and the concierge’s house. He then proceeded to identify the locations of 89 monuments in (some including multiple burials), noting them on his map as he walked the cemetery.

|

| Arnaud, 1815 |

In his 1816 guide to “day trips” from Paris, Dictionnaire Historique Topographique et Militaire de Tous les Environs de Paris, Pietresson de Saint-Aubin may have been the first writer of a general tour of Paris to focus on the four cemeteries of Vaugirard, Montmartre, Sainte-Catherine and of course, Père-Lachaise, as destinations worth exploring. (He included 37 entries for Père-Lachaise, “Mont-Louis.”) Building on his 1816 study, a decade later Saint-Aubin, too, would produce his own guide to Paris cemeteries: Promenade aux Cimetieres de Paris, aux Sepultures Royales de Saint-Denis et aux Catacombes.

These early efforts by Caillot and Saint-Aubin to identify the more well-known tombs at Père-Lachaise, hinted at the stories that lay beneath and around those handful of burials. Arnaud took their work to the next level and sought to locate those more well-known burials on a map as well as provide prints of some of them (making it easier to find them perhaps), all of which helped advance this new attention to who was buried where in Paris. And of course it also helped raised the exposure of Père-Lachaise as a place to consider spending eternity.

This interest in who was buried in Père-Lachaise, this new phenomenon of looking at death in a wholly different way through memorialization and pilgrimage, quickly culminated in a truly remarkable study of burials in the city's largest and most well-known cemetery.

1815-1816, Roger & Son raise the bar

A year before the transfer of the remains of Moliere, La Fontaine and Heloise and Abelard to Père-Lachaise in 1817, a father and son team published what must rank as one of the most unique study of any western cemetery. Published in Paris in 1816, Le Champ du Repos, ou Le Cimetiere de Mont-Louis, dit du Pere Lachaise by Roger et Fil is an exhaustive two-volume series listing every one of the more than 2,100 burials in the cemetery comprising what was then known about everyone buried in Père-Lachaise.

This work must certainly rank as the seminal study of the earliest burials in the cemetery: What the authors attempted to do, and very nearly succeeded, was to identify every known grave at the time, including even the temporary ones.

How did they do it?

First, they provided a handy map of the cemetery using major landmarks as a means of breaking the cemetery into manageable areas.

The various sections of the two volumes are broken down by series, which correspond to particular areas on the map, using letters A-F as identifiers that correspond to an outstanding landmark in that section:

- Lachapelle (Greffulhe chapel) - corresponds roughly to divisions present-day 40, 43, 45-46; plates 1-7, numbers 1-406

- Clary - divisions 20-30, 37-39, 48-53, 55; plates 8-16, nos. 407-783

- Delille - divisions 8-13; plates 17-24 , nos. 784-1179

- Lenoir-Dufresne - divisions 4, 57-58 (fosses communes); plates 25-36 , nos. 1180-1881

- Entree Projetee - divisions 1-3, 59 (fosses communes); plate 37, nos. 1182-2005

- Demauclere (mausoleum of madame, abbesse de l’abbaye royale de la Ferre) - divisions 7, 14, 16, 31, 35-36; plate 38, nos. 2006-2092

The two volumes record 2,174 burials in 2,091 entries; of that number 168 list no death year and 33 list a year but no date. Two hundred sixty-six locations are presently known. Almost all are individual entries (although there are occasions when multiple individuals are buried in the same location).

|

| figure 7 |

The finished sketched illustration (planche or “plate”) was given a number that corresponded to the grave listing and each drawing was then grouped together into a series of 37 illustration “maps” (figure 8). They even sketched out the markers for the seventeen burials that had no inscription at all and four where they couldn’t read the inscriptions.

|

| figure 8 |

|

| figure 9 |

By breaking the cemetery down into clearly defined “sections” they clearly attempted to narrowly locate each grave to be sure. For example, the most temporary of burials, the fosses commune, are nearly all found on plates 34-36 in what is today divisions 57-59. Of the 266 known locations we find some pattern to be sure: in the illustration figure 9, most of those graves are in fairly close proximity to each other (today).

On the other hand, to list two examples, of the 14 known burial locations found in division 4, the listings in Roger are scattered among plates 21, 23, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 and 37, while the 15 known burials in division 8 are found on plates 17, 18, 19 and 21.

It's therefore possible that there was some order in in where Rogers found the grave but it's not clear what that order was, at least not precisely. It's therefore likely that whatever systematic plan they used is not obvious today in how the graves are listed or sketched out.

And, while it’s probably safe to say that many of the graves were near one another in some fashion. beyond that we can’t be sure of exactly how the Rogers’ approached organizing their layouts.

Nor does it appear that they listed the gravesites by date of death. Here again there is occasionally a pattern, but that might be just coincidental to the actual burials themselves. Someone who died on one day, for example, might be buried near someone who died a week earlier simply by virtue of that space being more “available.”

For example, there appears a clear chronological order on plates 1-5: all but 12 of the 63 entries in plate 1 are listed in chronological order and the next four plates also demonstrate a chronology approach to listing them. The remaining plates, however, list burials with random death dates, with the occasional return to a chronological listing (see for example, plates 28-30). Indeed, nearly all the burials noted on plate 19 occurred February through March of 1815, yet the burials on plate 21 occurred between 1810 and 1814.

What complicates matters was the distinctive nature of Père-Lachaise itself (see for example figure 2). We know from early prints and observations by visitors during the early years of the cemetery that burials were scattered here-and-there, markers often set off by themselves, rather like many burial stones in Mt. Auburn Cemetery (Cambridge, MA) today. Thus, it’s probably safe to say that the earliest burials, aside from those “temporary” ones, were randomly located around the “grounds.”

|

| Mount Auburn Cemetery |

Finally, the Rogers’ attempt to locate and sketch each and every grave in the cemetery leaves us with the curious puzzle of why they left some burials out of their collection. A quick analysis of our sources shows that they did not record at least 9 listed by Caillot in 1809 and at least 41 listed on Arnaud’s map of 1815 are not found in Roger. For example, one of those notable graves listed on Arnaud’s map but not in Roger was wealthy negociant Pierre Gareau, who died on August 30, 1815. Gareau’s monument was then and still is topped by a life-size statue of a sitting woman with her hands brought up to her face.

It would seem that the Rogers did not refer to any older source when compiling their listings. But we’ll probably never know for certain.

What is certain is that the Rogers comprehensive and exhaustive efforts to find, identify, transcribe and then illustrate each and every monument and marker in the cemetery is nothing short of amazing. Their work should serve as inspiration for all of us who toil in the champs du repos, who seek to capture and preserve the memories of those who came before us, of “those who sleep the sleep that knows no waking.”

Just the beginning

Following the publication of Le champ du repos, the interest in identifying burials in Père-Lachaise intensified throughout the first half of the century. In 1821 F. G. T. de Jolimont published Les Mausolees de Paris, a detailed study of 51 notable burials in the cemetery with 42 accompanying prints. Beginning as early as 1822, Galignani, the Paris-based English-language publisher of guides to the city, began including itineraries to the major cemeteries, a trend they would continue in each annual edition for years to come. Baedeker guides would also pick up the same theme, including the major cemeteries, especially Père-Lachaise in its suggested itineraries.

In the 1820s Marchant de Beaumont published at least three separate guides to Père-Lachaise, and in 1832 Louis M. Normand produced a detailed architectural study of the larger monuments in the city’s cemeteries, including nearly many in Père-Lachaise. What may have been an attempt to emulate the work of the Rogers, in 1855 F. T. Salomon, published Le Père-Lachaise: Recueil General, an incredible effort to list more than 16,000 permanent concessions and then locate them all on the accompanying map.

Père-Lachaise long ago passed from its origins as a garden or pastoral cemetery and is today a true necropolis, a city of the dead with little houses lining paved streets just as you might find in any French village.

|

| division 19 and the left and 27 on the right |

Volume 1

Volume 2

For more information about the cemetery today visit: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cimetière_du_Père-Lachaise

Labels:

1816,

Caillot,

Pere Lachaise,

Pere-Lachaise,

Roger

Sunday, December 07, 2014

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)